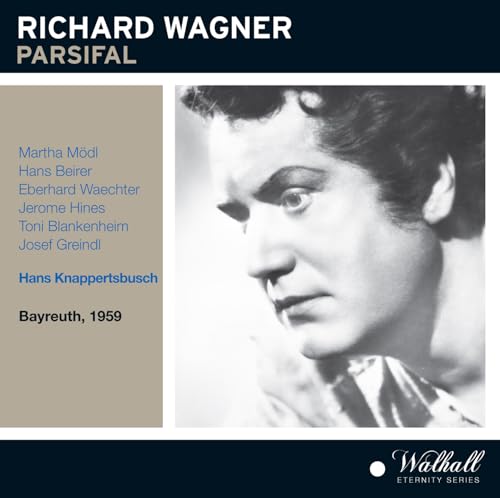

Wagner: Parsifal (Recorded 1959)

℗© 2014: Walhall Eternity Series

Artist bios

When Martha Mödl died at the age of 89, she had still not retired. The mezzo soprano turned dramatic soprano turned mezzo once more was a stage creature of rare magnetism. After a late start in music, she sang principal roles in the mezzo repertory during most of her thirties, but made a leap into the front rank of singing actresses with her engagement at the Bayreuth Festival, beginning with its re-opening in 1951. She alternated the three Brünnhildes and Isolde with Astrid Varnay and created a complex, tortured Kundry in Wieland Wagner's revolutionary production of Parsifal during the festival's first postwar season. Her ascent into dramatic soprano roles came gradually, first in such equivocally placed roles as Lady Macbeth and Venus, later in the higher reaches of the Ring heroines, and Isolde. While her beautiful, but softer timbre lacked the cutting edge of a Varnay, Nilsson, or Grob-Prandl, and failed her by the end of many performances, she brought a supreme measure of womanliness to her work. The all-out passion of her Isolde, captured live at the 1953 Bayreuth Festival, shares the top-most level of Wagner performance, along with more vocally reliable artists such as Leider, Flagstad, and the aforementioned trio of contemporaries.

Mödl studied at the Nuremberg Conservatory and made her debut as Hänsel in Remscheid in 1942. She was then 30 and had spent her earlier years as a secretary for a large business operation. That same year in Remscheid, she also sang Azucena, evidence that even at that point in her career, her vocal placement was somewhat in question. From 1945 to 1949, she was engaged at nearby Düsseldorf, where her roles included such diverse ladies as Dorabella and Klytemnestra, Marie (Wozzeck), and Eboli. Another of the roles in which she enjoyed success was Carmen and the gypsy subsequently served for her debut at Covent Garden in October 1949. Her London Carmen, which she had re-learned in English, was deemed surprisingly successful. Her Kundry in Berlin that same year also won high praise.

With her slender figure, immense and expressive eyes, and gift for powerful stillness, Mödl perfectly fitted Wieland Wagner's concept of simplified staging. She sang at Bayreuth until 1967 and her fame there led to other important engagements in Europe: Stuttgart, Edinburgh, and Vienna (where her Leonore re-opened the restored Staatsoper in 1955). She was admired by Wilhelm Furtwängler and with him recorded a complete Ring for Italian Radio, Fidelio, and a studio Die Walküre completed shortly before the conductor's death in 1954. Mödl's Metropolitan Opera career lasted just three seasons and a mere dozen performances. The high-lying Siegfried Brünnhilde with which she made her first appearance on January 30, 1957, was the most problematic of the three Ring heroines and her modern style of acting seemed out of place in the aging Metropolitan production. By that time, too, and in two following seasons, she was experiencing difficulties with her high register. By the early '60s, she had dropped back into mezzo roles, her voice sounding increasingly frayed, but her histrionic acuity entirely intact. In subsequent years, she sang mezzo parts large and small and even presented herself in Fiddler on the Roof. She participated in premieres of works by Von Einem, Eötvös, Fortner, Cerha, Klebe, and Reimann. Just weeks before her death, she had been acclaimed as the Nurse in a Berlin production of Boris Godunov.

Hans Knappertsbusch (1888 - 1965) was one of the most renowned and beloved conductors of the German Romantic repertoire in the mid-twentieth century. Although he grew up playing and loving music, his parents objected to the notion of a musical career. Consequently, Knappertsbusch studied philosophy at Bonn University; in 1908, however, he entered the Cologne Conservatory, where he studied conducting with Fritz Steinbach.

Knappertsbusch began his career as a staff conductor at the Mülheim-Ruhr Theater (1910 - 1912) and then as opera director in his home town (1913 - 1918). Equally important to his development were his summers as an assistant to director Siegfried Wagner and conductor Hans Richter at the Bayreuth Festival. Knappertsbusch's Bayreuth activities led to his taking part in the Netherlands Wagner Festivals in 1913 and 1914. In 1918 Knappertsbusch went to Leipzig and, in 1919, to Dessau, where he became music director in 1920. When Bruno Walter left Munich in 1922, Knappertsbusch was asked to assume the position as music director there.

Knappertsbusch's personality was easygoing; he was notably free of the restlessness and undue ambition that often attended a rising career such as his. He was content mainly to stay in Munich, with the result that he never became as well-known as many of his colleagues. In any case, Munich fully appreciated Knappertsbusch's talents, and he was named conductor for life. However, he refused several demands by the Nazis and was fired from his "lifetime" post in 1936. He conducted a memorable "Salome" in Covent Garden in 1936 and 1937 and guest conducted elsewhere in Germany, but was content to maintain a low profile during the Nazi regime. He left Germany after the Munich debacle, settling in Vienna where he frequently conducted the Philharmonic and the Vienna State Opera. Knappertsbusch's career was again impacted by the Nazis when Germany took over Austria over in 1938; however, he was mostly able to steer of trouble with the Nazis.

Knappertsbusch gained a reputation for broad, magisteral performances of Bruckner and, more and more, seemed to represent the traditional style of unhurried Wagner performances. He was famous for disliking rehearsals, often cutting them short; his orchestral players maintained that this was not the result of laziness, but of complete security in his interpretation and trust of the players. His performances were therefore not rigidly preconceived, but instead had a remarkable freshness and spontaneity.

When the Bayreuth Festivals reopened in 1951, Knappertsbusch worked closely with Wieland Wagner on orchestral matters (though the conductor was known to dislike Wagner's spare, revolutionary stage productions). Knappertsbusch's most outstanding recording is his stereo account of Wagner's "Parsifal" from the Bayreuth stage. ~ Joseph Stevenson

Josef Greindl, with a voice mellower and less cutting than those of Gottlob Frick or Kurt Böhme, nonetheless became a dominant presence in the heaviest German bass roles during the 1950s and 1960s. A wide vibrato bothered some listeners who were sensitive to such matters, but Greindl was a savvy enough artist to subdue the effect in all but the most sustained passages and he was a canny presence. His Hagen exuded evil, while his Sarastro had a warmth and dignity that clarified the role as few others did. His occasional ventures into Italian opera largely took place in Germany and primarily at a time in which Italian opera was sung there in the vernacular. Greindl sang the leading bass roles in two essential Ring cycles preserved on disc, first under Furtwängler in 1953 and under Clemens Krauss at Bayreuth in 1954. Studies with bass Paul Bender, a former leading artist in Munich, and Wagnerian soprano Anna Bahr-Mildenburg prepared Greindl for his debut as Hunding in a 1936 Krefeld production. From 1938 to 1942, the young bass was engaged at Düsseldorf. In 1942, Greindl began a long association with Berlin, first at the Staatsoper (until 1949) and thereafter at the Berlin's Städtische Oper. His debut at the Bayreuth Festival came as Pogner in 1943, but his prominent years there began in earnest in 1951. Concentrating his career in Europe, Greindl spent only one season at the Metropolitan Opera: in 1952, Heinrich and Pogner sufficed for his New York opera appearances. Later, however, he sang in Chicago, where his Daland and Alvise (in Italian, of course) were heard at the Lyric Opera in 1959. San Francisco heard him only in 1967 when his King Marke was described as "wobbly," although his Baron Ochs opposite Régine Crespin's Marschallin was found more satisfactory. In Berlin, the bass was much admired for his Boris Godunov. In the latter years of his Bayreuth affiliation, he abandoned Pogner for Hans Sachs, managing the tiring tessitura and enormous length of the role with skill and creating a positive portrait of the master cobbler. In 1973, Greindl was appointed a professor of singing at Vienna's Hochschule für Musik.

Jerome Hines was one of the best known and most durable of American bass-baritones, known for his rich, powerful, unforced voice and his psychologically penetrating acting performances.

Jerome Albert Link Heinz (as he was born) loved singing but was turned down by his junior high school glee club because his voice didn't blend.

He studied at the University of California Los Angeles, with a degree in science, having taken chemistry, physics, and mathematics. He taught chemistry at UCLA for a year, then worked as a chemist for an oil company.

However, while he had been at UCLA he took singing lessons from Gennaro Curci, and at the age of 20 debuted at the San Francisco Opera in 1941; during that season he sang as Monterone in Verdi's Rigoletto and in Tannhäuser. After that, he was invited to sing with several orchestras, including the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and with the New Orleans Opera, which convinced him to concentrate on singing as his career. He won the Caruso Award in 1946, resulting in his Metropolitan Opera audition and debut in 1947 as The Sergeant in Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. Irving Kolodin's review made as much mention of his tall height as of his "able singing." In December, he was given the role of Méphistophélès in Gounod's Faust. The New York Times judged that the role was "still somewhat beyond him" but praised his singing ability and said that "much can be expected" of him.

He soon proved himself a reliable comprimario singer the next season, appearing 45 times in ten roles, including the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlos, Don Basilio in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, the Commendatore in Don Giovanni, and Nick Swallow in Peter Grimes. He also appeared in these years in Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, and Mexico City. His reputation soared when he was selected by conductor Arturo Toscanini to sing some of his concerts and appear in his 1953 recording of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis.

Also in 1953 he made major European appearances at the Glyndebourne and Edinburgh Festivals.

Complications in his career development arose in 1951, when the Montreal-born American bass-baritone George London appeared at the Met. With the presence of London, Hines, and Ezio Pinza -- singers so great that in a later day they would surely have been marketed as the "Three Basses" -- it took Hines a few more years before he moved out of roles like the Grand Inquisitor and the Sergeant into the leading roles, like Philip II and Boris himself.

In the mid-1950s, he added the major Wagnerian bass-baritone parts to his repertoire, including Gurnemanz, King Marke, and Wotan, all of which he sang at Bayreuth. In 1962, he became the second American singer to portray Boris Godunov at the Bolshoi Opera in Moscow; George London had preceded him in 1960.

Hines went on to sing 45 roles in hundreds of performances at the Metropolitan. He holds the record for the most consecutive seasons there by any major artist at 41. His last appearance was on January 24, 1987 as Sparafucile in Rigoletto.

He was a highly religious man who is reputed to have walked out of a production at the Met due to his objections over the "lewd" qualities of the choreography. He wrote an opera, I Am the Way, on the life of Christ. His autobiography, This is my Story, this is my Song, was published in 1968, and he wrote two highly regarded books on the art of singing, Great Singers on Great Singing (1982) and The Four Voices of Man (1997).

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?