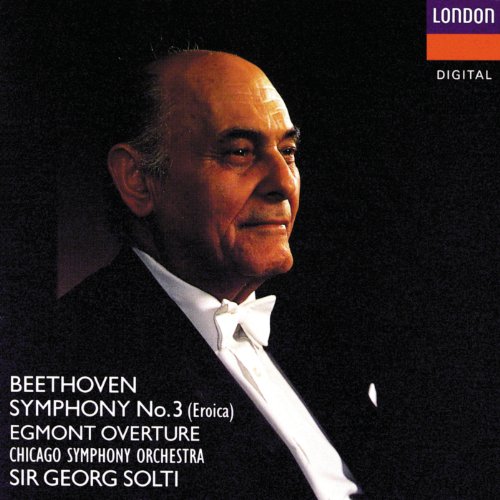

Beethoven: Symphony No.3/Egmont Overture

℗ 1976 Decca Music Group Limited © 1988 Decca Music Group Limited

Artist bios

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is one of the three most acclaimed orchestras in America and one of the few serious rivals the New York Philharmonic has had in its long history. Curiously, the histories of the two orchestras are somewhat intermingled.

Theodore Thomas had organized and led orchestras in New York during the 1870s and 1880s, competing with the Philharmonic Society of New York for audiences, soloists, and American premieres of works. His orchestra did very well as a major rival to the group that would become the New York Philharmonic. The orchestra visited Chicago during several seasons, and it was intended that he would be music director of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in that city. However, in 1891, he abandoned New York entirely in favor of Chicago and arrived as the first conductor of what was then called the Chicago Orchestra. Thomas held that position until his death in 1905. In his honor, the Chicago Orchestra changed its name to the Theodore Thomas Orchestra in 1906. Six years later, the group was renamed the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

It was under the leadership of Thomas' assistant, Frederick Stock, that the Chicago Symphony's modern reputation was formed. From 1905 until his death in 1942, Stock led the orchestra in decades of programs that featured not only the established classics but the American premieres of many post-romantic works. Additionally, Stock raised the level of performance and the financial status of his players and established the orchestra in a major teaching role for aspiring musicians in its home city. Its recordings were relatively few in number because the long-playing record -- central to the appreciation of classical music -- had not yet been invented, which means there is little evidence by which modern listeners can judge the work of the orchestra during this period, but some of the recordings from that era were among the best in the world at the time. Among the few available from the period on major labels are the Beethoven Piano Concertos Nos. 4 and 5 on the BMG label, featuring soloist Arthur Schnabel with Stock conducting.

Stock's death in 1942 precipitated a difficult decade for the orchestra. Apart from the general complications of World War II, it had a great deal of trouble finding acceptable leadership. Désiré Defauw lasted for only four years, from 1943 until 1947, and Artur Rodzinski (best known for his leadership of the New York Philharmonic) was in the job for only one year (1947-1948). Rafael Kubelik served three years as music director from 1950 until 1953, but his gentlemanly manner and decidedly modern, European-centered taste in music proved unsuited to the players, critics, and management -- although it was under Kubelik that the orchestra made its first successful modern recordings, for the Mercury label, many of which were reissued in the mid-'90s.

Fritz Reiner became the music director of the Chicago Symphony in 1953, beginning the modern renaissance and blossoming of the orchestra. Under Reiner, the orchestra's playing sharpened and tightened, achieving a clean, precise, yet rich sound that made it one of the most popular orchestras in the United States. The Chicago Symphony under Reiner became established once and for all as an international-level orchestra of the first order, rivaling the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Boston Symphony. Moreover, Reiner's arrival with the orchestra coincided with its move to RCA Victor, which, in 1954, was beginning to experiment with stereo recording. With Reiner as conductor, these "Living Stereo" recordings -- characterized by vivid textures, sharp stereo separation, and microphone placement that gave the impact of a live performance -- became some of the best-selling classical albums of all time and have since been reissued numerous times on compact disc to new acclaim from critics and listeners, more than a generation removed from their original era.

Reiner's death in 1963 led to another interregnum period, during which conductor Jean Martinon led the orchestra (1963-1968). In 1969, Sir Georg Solti joined the orchestra as its music director. Under Solti, the orchestra's national and international reputations soared, as did its record sales. Reiner had begun the process of cultivating the burgeoning audience for late-romantic composers such as Mahler, but it was with Solti that the works of Mahler and Bruckner became standard fare in the orchestra's programs, right alongside those of Beethoven and Mozart. The playing standard achieved during Solti's tenure, in concert and recordings, was the highest in the history of the orchestra. Additionally, the orchestra under Solti began a quarter-century relationship with London Records that resulted in some of the best-sounding recordings of the era. Solti's approach to performance was very flamboyant yet intensely serious -- even his performances of lighter opera and concert overtures strike a perfect balance between broad gestures and finely wrought detail, attributes that have made him perhaps the most admired conductor of a major American orchestra, if not the most famous (Leonard Bernstein inevitably got more headlines during the 1960s, especially with his knack for publicity). Solti was both popular and respected, and his tenure with the Chicago Symphony coincided with his becoming the winner of the greatest number of Grammy Awards of any musician in history (he also recorded with orchestras in London and Vienna). Daniel Barenboim succeeded Solti and served as music director from 1991 until 2006, with Solti transitioning to the post of music director emeritus. Bernard Haitink was named the orchestra's first principal conductor, holding this position from 2006 through 2010. Riccardo Muti was chosen as the tenth music director in the orchestra's history in 2010.

As with other major American orchestras, the Chicago Symphony found itself competing with its own history, especially where recordings are concerned. Reissues of its work under Reiner and Solti continue to sell well and are comparable or superior to the orchestra's current recordings in sound and interpretive detail. Even the early-'50s recordings under Kubelik were reissued by Mercury in the late '90s, while RCA-BMG and some specialty collector's labels have re-released the recordings under Stock. The recordings of Solti and Reiner leading the Chicago Symphony are uniformly excellent, and virtually all of them can be recommended. The orchestra also maintains composer-in-residence and artist-in-residence partnerships; in 2023, Jessie Montgomery occupied the former, and Hilary Hahn the latter. ~ Bruce Eder

The events of Beethoven's life are the stuff of Romantic legend, evoking images of the solitary creator shaking his fist at Fate and finally overcoming it through a supreme effort of creative will. His compositions, which frequently pushed the boundaries of tradition and startled audiences with their originality and power, are considered by many to be the foundation of 19th century musical principles.

Born in the small German city of Bonn on or around December 16, 1770, he received his early training from his father and other local musicians. As a teenager, he earned some money as an assistant to his teacher, Christian Gottlob Neefe, then was granted half of his father's salary as court musician from the Electorate of Cologne in order to care for his two younger brothers as his father gave in to alcoholism. Beethoven played viola in various orchestras, becoming friends with other players such as Antoine Reicha, Nikolaus Simrock, and Franz Ries, and began taking on composition commissions. As a member of the court chapel orchestra, he was able to travel some and meet members of the nobility, one of whom, Count Ferdinand Waldstein, would become a great friend and patron to him. Beethoven moved to Vienna in 1792 to study with Haydn; despite the prickliness of their relationship, Haydn's concise humor helped form Beethoven's style. His subsequent teachers in composition were Johann Georg Albrechtsberger and Antonio Salieri. In 1794, he began his career in earnest as a pianist and composer, taking advantage whenever he could of the patronage of others. Around 1800, Beethoven began to notice his gradually encroaching deafness. His growing despondency only intensified his antisocial tendencies. However, the Symphony No. 3, "Eroica," of 1803 began a sustained period of groundbreaking creative triumph. In later years, Beethoven was plagued by personal difficulties, including a series of failed romances and a nasty custody battle over a nephew, Karl. Yet after a long period of comparative compositional inactivity lasting from about 1811 to 1817, his creative imagination triumphed once again over his troubles. Beethoven's late works, especially the last five of his 16 string quartets and the last four of his 32 piano sonatas, have an ecstatic quality in which many have found a mystical significance. Beethoven died in Vienna on March 26, 1827.

Beethoven's epochal career is often divided into early, middle, and late periods, represented, respectively, by works based on Classic-period models, by revolutionary pieces that expanded the vocabulary of music, and by compositions written in a unique, highly personal musical language incorporating elements of contrapuntal and variation writing while approaching large-scale forms with complete freedom. Though certainly subject to debate, these divisions point to the immense depth and multifariousness of Beethoven's creative personality. Beethoven profoundly transformed every genre he touched, and the music of the 19th century seems to grow from his compositions as if from a chrysalis. A formidable pianist, he moved the piano sonata from the drawing room to the concert hall with such ambitious and virtuosic middle-period works as the "Waldstein" (No. 21) and "Appassionata" (No. 23) sonatas. His song cycle An die ferne Geliebte of 1816 set the pattern for similar cycles by all the Romantic song composers, from Schubert to Wolf. The Romantic tradition of descriptive or "program" music began with Beethoven's "Pastoral" Symphony No. 6. Even in the second half of the 19th century, Beethoven still directly inspired both conservatives (such as Brahms, who, like Beethoven, fundamentally stayed within the confines of Classical form) and radicals (such as Wagner, who viewed the Ninth Symphony as a harbinger of his own vision of a total art work, integrating vocal and instrumental music with the other arts). In many ways revolutionary, Beethoven's music remains universally appealing because of its characteristic humanism and dramatic power. ~ Rovi Staff

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?