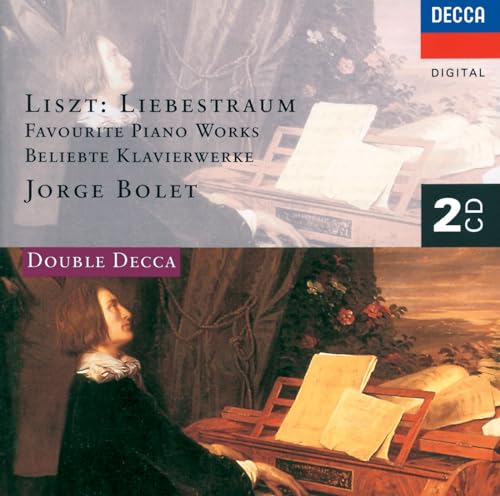

Liszt: Liebestraum - Favourite Piano Works

ÔäŚ This Compilation 1995 Decca Music Group Limited ┬ę 1995 Decca Music Group Limited

Artist bios

Virtuoso pianist Jorge Bolet began his keyboard studies at the age of nine. His progress excited his local teachers and he received a scholarship at the age of 12 to study in the United States, at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. There his piano teacher was David Saperton. Beginning in 1932 he studied with Leopold Godowsky and Moritz Rosenthal, and, briefly, with Rudolf Serkin. He won the Naumburg Prize in 1937 and the Josef Hofmann Award in 1938. He became Rudolf Serkin's teaching assistant at the Curtis Institute in 1939. In 1942 he joined the United States armed forces. After the end of the war he was a part of the U.S. cccupying forces in Japan. There, he conducted the first performance in that country of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado. He resumed his piano career after taking private lessons with Abram Chasins. Over a period of a few years he developed a reputation as a virtuoso player of astonishing power, able to play the most difficult works by Liszt with an impression of natural ease that left the feeling that there was no limit to his pianistic range. He became the head of the piano faculty at Curtis, and also was on the piano faculty of Indiana University at Bloomington. While in the United States he preferred the pronunciation "George" for his first name.

Until nearly the end of his life he maintained a major performing and recording career. His recordings were primarily for the Decca (London) company. He produced many estimable performances, notably those of the major piano works by Franz Liszt, as well as concertos and other works. As exciting as some of these recordings were, he was an artist whose full range of brilliance was not caught by the microphone.

Liszt was the only contemporary whose music Richard Wagner gratefully acknowledged as an influence upon his own. His lasting fame was an alchemy of extraordinary digital ability -- the greatest in the history of keyboard playing -- an unmatched instinct for showmanship, and one of the most progressive musical imaginations of his time. Hailed by some as a visionary, reviled by others as a symbol of empty Romantic excess, Franz Liszt wrote his name across music history in a truly inimitable manner.

From his youth, Liszt demonstrated a natural facility at the keyboard that placed him among the top performing prodigies of his day. Though contemporary accounts describe his improvisational skill as dazzling, his talent as a composer emerged only in his adulthood. Still, he was at the age of eleven the youngest contributor to publisher Anton Diabelli's famous variation commissioning project, best remembered as the inspiration for Beethoven's final piano masterpiece. An oft-repeated anecdote -- first recounted by Liszt himself decades later, and possibly fanciful -- has Beethoven attending a recital given by the youngster and bestowing a kiss of benediction upon him.

Though already a veteran of the stage by his teens, Liszt recognized the necessity of further musical tuition. He studied for a time with Czerny and Salieri in Vienna, and later sought acceptance to the Paris Conservatory. When he was turned down there -- foreigners were not then admitted -- he instead studied privately with Anton Reicha. Ultimately, his Hungarian origins proved a great asset to his career, enhancing his aura of mystery and exoticism and inspiring an extensive body of works, none more famous than the Hungarian Rhapsodies (1846-1885).

Liszt soon became a prominent figure in Parisian society, his romantic entanglements providing much material for gossip. Still, not even the juiciest accounts of his amorous exploits could compete with the stories about his wizardry at the keyboard. Inspired by the superhuman technique -- and, indeed, diabolical stage presence -- of the violinist Paganini, Liszt set out to translate these qualities to the piano. As his career as a touring performer, conductor, and teacher burgeoned, he began to devote an increasing amount of time to composition. He wrote most of his hundreds of original piano works for his own use; accordingly, they are frequently characterized by technical demands that push performers -- and in Liszt's own day, the instrument itself -- to their limits. The "transcendence" of his Transcendental Etudes (1851), for example, is not a reference to the writings of Emerson and Thoreau, but an indication of the works' level of difficulty. Liszt was well into his thirties before he mastered the rudiments of orchestration -- works like the Piano Concerto No. 1 (1849) were orchestrated by talented students -- but made up for lost time in the production of two "literary" symphonies (Faust, 1854-1857, and Dante, 1855-1856) and a series of orchestral essays (including Les pr├ęludes, 1848-1854) that marks the genesis of the tone poem as a distinct genre.

After a lifetime of near-constant sensation, Liszt settled down somewhat in his later years. In his final decade he joined the Catholic Church and devoted much of his creative effort to the production of sacred works. The complexion of his music darkened; the flash that had characterized his previous efforts gave way to a peculiar introspection, manifested in strikingly original, forward-looking efforts like Nuages gris (1881). Liszt died in Bayreuth, Germany, on July 31, 1886, having outlived Wagner, his son-in-law and greatest creative beneficiary.

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?