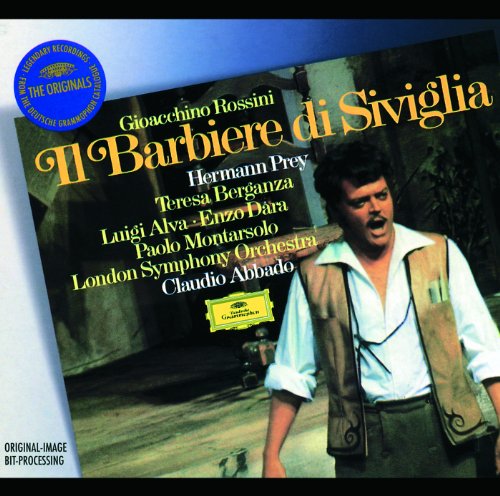

Rossini: Il Barbiere Di Siviglia

℗ 1972 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin © 1998 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin

Artist bios

Mezzo-soprano Teresa Berganza's career always had something of a Spanish flavor to it, even though she excelled in Mozart and Rossini roles and other elements of the traditional repertory. She consistently championed Spanish music, from zarzuela to the songs of Granados and Falla. She also sang the title role of Carmen frequently, bringing her own unique sense of the character to both stage and recordings. A musician of unusual breadth and ability, Berganza was an accomplished pianist and organist and even studied conducting and composition. Her voice, which had an impressive upper extension, managed to cross boundaries as well: in 1960, she was offered the role of Violetta -- a mainstay of the soprano repertory -- in Verdi's La traviata at La Scala in Milan.

Berganza was born in Madrid on March 16, 1935. She studied at the Madrid Conservatory under Lola Rodriguez Aragon, who herself studied with Elisabeth Schumann. Berganza credited her teacher with the complete process of her development, from a raw talent to a polished artist; throughout her career, she continued to study with Aragon, developing interpretations or working out minor vocal problems. Berganza made her professional debut in 1956 at the Madrid Athenaeum in Schumann's song cycle Frauenliebe und -Leben, and made her operatic debut at the Aix-in-Provence Festival as Dorabella in Così fan tutte. She made her Glyndebourne debut in 1958 as Cherubino in Le Nozze di Figaro.

In the same year, she made her U.S. debut in Dallas, singing the comprimario role of Neris in a production of Medea. The Medea was Maria Callas, and Berganza later declared that she never learned as much about musical drama and stage discipline as from Callas, who treated her "like a younger sister," even insisting that Berganza be allowed to portray Neris as a young woman close to Medea's own age, rather than an older, matronly figure, as was customary. Berganza made her Covent Garden debut as Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia in 1960; throughout the 1960s and early '70s, she sang mostly Rossini and Mozart. She made her Met debut as Cherubino in 1967.

Berganza first sang Carmen in 1977 and described it later as a deeply liberating experience -- personally as well as musically. In preparing the role, she visited Seville to observe Romani women, read the original novel by Prosper Mérimée, and studied the score deeply. She developed her own perceptions of Carmen: she was a free spirit within a restrictive culture, but far from being a prostitute or a tramp, and even possessing a certain sweetness. While many critics applauded her presentation, others found it lacking in blood and guts -- too "ladylike." She brought the same kind of original thinking to the role of Zerlina in Don Giovanni, and in the famous Joseph Losey film, she sang her as a fully mature and sensual young woman, rather than a simple and bedazzled girl.

Berganza was also a prominent recitalist, specializing in Spanish song, but she also sang Mussorgsky and others. Her first husband, Félix Lavilla, whom she met at the Madrid Conservatory, was also her accompanist for many years. Although her last significant stage performance was in 1992, she continued to give recitals and teach master classes into the 2000s and officially retired from the stage in 2008. She was protective of her voice and what she allowed audiences to hear throughout her career, which contributed to its longevity. Among her recordings, her Rosina and her collection of Spanish songs on Claves are both outstanding. Berganza died on May 13, 2022, at the age of 89. ~ Anne Feeney & Patsy Morita

Founded in 1904 and therefore the oldest of the city's symphony orchestras, the London Symphony Orchestra became world-renowned for recordings that date back to early gramophone records in 1912. Amid decades of diverse classical programming that followed, including performances for radio and TV, the orchestra also became known for its appearances in numerous film scores, including the Star Wars series. The LSO also tours and first visited North America in 1912 (narrowly avoiding passage on the Titanic).

The ensemble's direct antecedent was the Queen's Hall Orchestra, formed in 1895 for conductor Henry Wood's series of Promenade Concerts. The summer series was so successful that a series of weekly Sunday afternoon concerts was established the same year. The orchestra, however, had never become a permanent group; its members could and often did send other musicians to substitute for them at concerts. In 1904, Wood attempted to end this practice, prompting 46 members to leave and form their own orchestra.

The London Symphony Orchestra was organized as a self-governing corporation administered by a board selected by the players. They arranged for the great Hans Richter to conduct the inaugural concert, and continued to engage a variety of conductors, practically introducing the concept of the guest conductor to the London musical scene. Soon, though, the title and post of principal conductor was established for Richter. The LSO's connection with the BBC goes back to 1924 when Ralph Vaughan Williams conducted the orchestra in the premiere broadcast performance of his Pastoral Symphony. It was the unofficial orchestra in residence for the BBC until the formation of the BBC Symphony in 1930 and continued to broadcast concerts and provide background music for many BBC productions. Other conductors most associated with the orchestra's first few decades include Edward Elgar and Thomas Beecham. During World War II, Wood was welcomed for a series of concerts.

The War took its toll on orchestra membership as it had the general populace, and a concurrent drop in private funding led to increased reliance on the state arts council. This eventually led to structural reorganization in the 1950s, resulting in increased professional standards and the abandonment of profit-sharing; players became salaried employees. The revamped orchestra made only its second tour of the United States in 1963 (the first had been in 1912), and in 1964 embarked on its first world tour. In the mid-1960s the city of London broke ground for the Barbican Arts Centre, intended as the LSO's permanent home. The building was an architectural and acoustic success, and since 1982 has provided the orchestra the solid base it lacked during the first 70-plus years of its existence. The venue opened under principal conductor Claudio Abbado, who took over for André Previn in 1979.

In the meantime, the orchestra made its Star Wars debut, performing John Williams' score for the original 1977 film. While the organization had recorded its first film score in 1935 (H.G. Wells' Things to Come) and appeared in such classics as The Bridge on the River Kwai, Doctor Zhivago, and The Sound of Music, Star Wars won three Grammys, an Academy Award, and a BAFTA, among many other accolades, sold over a million copies in the U.S. and over 100,000 in the U.K., and endures as a touchstone in modern film music. The LSO went on to record music for the franchise's entire first two trilogies as well as films like 1981's Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1993's Schindler's List, 1997's Titanic, and select installments of the Harry Potter series.

During the tenure of Colin Davis, who was named principal conductor in 1995, the LSO established its own record label, LSO Live. Dvorák's Symphony No. 9, recorded at Barbican Centre in 1999 and released in 2000, bears catalog number 0001. Their 2000 recording of Berlioz's Les Troyens won two Grammys in 2002, and Verdi's Falstaff took home the Best Opera Grammy in 2006. In 2007, Davis took the position of orchestra president, its first since Leonard Bernstein's passing in 1990, and Valery Gergiev became principal conductor.

Also known for crossing over into rock, jazz, and Broadway, among other categories, they followed hit recordings such as Symphonic Rolling Stones and Gershwin Fantasy (with Joshua Bell) with albums like 2017's Someone to Watch Over Me, which had them accompanying archival recordings of Ella Fitzgerald. ~ Marcy Donelson, Joseph Stevenson & Corie Stanton Root

Hermann Prey was a truly versatile performer -- aside from lieder, sacred music, operetta, and opera, toward the end of his career he became a beloved television host and comedian in his native Germany. He was a particularly warm and genial recitalist, and was known for varying his lieder interpretations according to the moods and reactions he picked up from the audience. Such lieder performances were at the core of his work as a singer, although he was also a gifted actor on the opera stage, and was noted for his very human, rather than buffoonish interpretation of Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger. He and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau were near-contemporaries, sharing almost the same repertoire. Though they rarely sniped at one another in public or threw temper tantrums over the other's publicity (unlike many of their precedents or successors), there was a certain tension between them, which did ease as time progressed, and both were generally acknowledged as different artists who brought different strengths to music, rather than one being a less successful version of the other. He was also a noted teacher, both of singing technique and lieder interpretation.

While his father had no special interest in music, his mother was a music lover, particularly devoted to vocal music. At school, Prey sang in the choir, with occasional solos, and at the age of eleven successfully auditioned for the highly selective Berlin Mozart Choir. The war disrupted all of this, but Prey still sang whenever possible and also played in some amateur bands. After school, he applied to the local music conservatory, and while he was not accepted, the judges recommended that he study with a young teacher, Harry Gottschalk, though Gottschalk was still in college at the time. One of the first tasks was determining whether Prey was a tenor or a baritone, and while his voice did deepen throughout his career, he kept a strong upper register. Gottschalk's teaching focused on vocal exercises and songs, and Prey made enough progress that when he re-auditioned for the conservatory in 1948, he was accepted. At the conservatory he greatly improved his aural training and intonation, and developed a wide repertoire of musical styles, from the medieval to contemporary. Here Prey received his first in-depth introduction to lieder, and it was while he was a student that he decided that 19th century lieder would be the core of his career.

In 1950 he made his first professional concert appearance in a concert at Grunewald Castle, singing the baritone part of Paul Hoffer's Woodland Serenade. During this period, when he was getting as much experience as he could, he also sang a good deal of popular music, and was even urged to become a popular rather than a classical singer. Though his heart remained with lieder and, to a lesser extent, opera, he maintained an interest in popular music, performed and recorded it to some extent throughout his career, and was steadfast in maintaining that a singer need be neither "just classical" or "just popular." Early in 1952, he was expelled from the conservatory for having covertly continued his studies with Gottschalk, whose methods of vocal teaching he preferred to that of the conservatory professors. By that time, however, he had enough experience and exposure as a singer that his career was not particularly affected.

Shortly after this, he won the first prize in the American Army's German youth organization's Mastersinger Competition (out of 3,000 singers who auditioned), which brought him even more publicity, and so many new offers for engagements that unlike most students, he was turning down more offers than he accepted. One of the ones he accepted was for the Hesse State Theater in Wiesbaden, and he made his stage debut as Moruccio in d'Albert's Tiefland. In late 1952, as part of the prize package of the Mastersinger Competition, he made a four-week tour of the United States, where he made his first television appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, as well as singing in several concerts. Returning to Germany in January of 1953, he auditioned at the Electrola Studios, where he was engaged for several recordings, and in 1954 he made his first recording for EMI, in The Gypsy Baron, as well as singing his first lead role with the Hamburg Opera, Don Carlo in Verdi's La Forza del Destino.

In 1960 he made his Met debut as Wolfram in Tannhauser, and in 1962, he made his Salzburg Festival debut as Gugliemo in Cosi Fan Tutte and recorded Schumann's Dichterliebe for Electrola. In 1963, he made his San Francisco opera debut as Rossini's Figaro. He sang Papageno for the first time in 1964, and it was to become his most popular operatic role; in 1965, he sang Wolfram in his Bayreuth debut.

He first met Fritz Wunderlich in 1959, and they two became very close friends as well as professional associates. In his autobiography (Premierefieber/First Night Fever), in the chapter entitled "Amico Fritz," he described his desolation at Wunderlich's untimely death. He and Wunderlich had recorded an album of Christmas music, which was published about a month after Wunderlich's death. Prey wrote a tribute to Wunderlich on the record sleeve, ending "We were going to take the world by storm. We were to become the Castor and Pollux of song. But fate would have it otherwise. I must remain as the lonely and abandoned twin. I mourn the loss of a friend and brother singer, whom no one can ever replace." Fortunately, they made several recordings and radio broadcasts together, many of which are available on CD.

In 1967, he made his first television show, Schaut Her, Ich's Bin, which became wildly popular. In 1970, made an eight-LP collection of folk songs for Philips, and in 1971 he made a belated debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, as Rossini's Figaro. He made a still more belated debut in the same role at Covent Garden in 1973. During the '70s and '80s, he continued to record and present recitals, even adding new roles to his repertoire such as Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger. In 1976, Phonogram released a long-time project of Prey's, a recording of The Prey Lied Edition, a collection of 450 German songs, from Minnesinger compositions to modern works. That same year, he established the Schubertiade Festival at Hohenems, which he directed until 1981, when he and the management disagreed over some of the festival's artistic aims, specifically Prey's wish to present all of Schubert's songs in strict chronological order. He made his directorial debut in 1988 in Salzburg, directing Le Nozze di Figaro. He died unexpectedly in 1993 of heart failure. He and his wife, Barbel, had three children, one of whom, Florian Prey, is himself a singer, whose timbre has some of the same richness of his father's voice.

While he left a number of recordings, unfortunately the Prey Lieder Edition is not currently available on CD. However, EMI released some of his finer Schubert and Brahms recordings in CDZC 68432, and on Intercord Klassische Diskothek he recorded an excellent collection of lieder by Loewe, who was largely overshadowed by Schubert, Schumann, Wolf, and Brahms, but whose music Prey considered greatly underappreciated. In 1988, EMI also released a selection of opera arias (545-CDM), mostly recorded in German. While his rendition of the Toreador Song sounds avuncular rather than swaggering, the other selections, drawn from both his regular repertoire (Die Zauberflaute, Le Nozze di Figaro) and works not associated with his career (Faust, Pique Dame) are excellent. ~ Ann Feeney

One of the top conductors of the 20th century, Claudio Abbado left an enormous recording catalog covering a wide range of composers from the Classical era to the early modern period. He was chief conductor and artistic director of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from 1989 to 2002.

Abbado was born in Milan, Italy, on June 26, 1933, into an old family that traced its roots to Moorish-era Spain. His father, Michelangelo Abbado, was a prominent violinist and a professor at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory, and his mother, Maria Carmela Savagnone, was a skilled pianist. Abbado and his brother Marcello, who also became a pianist and composer, had their first lessons from their father. Their careers were interrupted by the Nazi occupation of Milan during World War II; Abbado's mother was arrested for giving refuge to a Jewish child, and the young Claudio became a confirmed anti-fascist who scrawled "Viva Bartók" on a wall and triggered an unsuccessful manhunt. He enthusiastically attended performances at Milan's La Scala opera house and, when he could, orchestral rehearsals led by the likes of Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler.

Abbado went on to the Milan Conservatory, graduating in 1955 as a pianist. He also studied conducting with Antonio Votto. He then moved to Vienna, studying piano with Friedrich Gulda and conducting with Hans Swarowsky at the Vienna Academy of Music. He and his classmate Zubin Mehta joined the school's chorus so that they could observe the conducting technique of such legends as Bruno Walter and Herbert von Karajan. After more classes at the Chigiana Academy in Siena, Italy, he made his debut as a conductor in Trieste, leading a performance of Prokofiev's Love for Three Oranges. In the summer of 1958, Abbado had a major breakthrough when he won the Koussevitzky Conducting Competition at the Tanglewood Festival in Massachusetts. That led to various European conducting engagements and, in 1960, to a conducting debut at La Scala.

Advancement in the Western hemisphere came in 1963 when Abbado was awarded the Dmitri Mitropoulos Prize. That came with the chance to conduct the New York Philharmonic for five months. In 1965, Abbado conducted the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra for the first time at Austria's Salzburg Festival. In the late '60s, he conducted several productions at La Scala, and in 1971, he was named the company's music director. He raised the opera orchestra's standards and formed it into an independent Orchestra della Scala, which often performed contemporary works. Abbado also became principal conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic in 1971, and he also began to appear frequently with the London Symphony Orchestra, becoming its principal conductor in 1979 and later its music director. His recording career stretched far back into the LP era; with the London Symphony, he made a notable early recording in 1972 of Rossini's opera La Cenerentola. Abbado also found time to conduct the European Community Youth Orchestra, the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, and the Gustav Mahler Youth Chamber Orchestra, and he mentored many young musicians.

Abbado served as principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1982 to 1986. He was then appointed music director of the Vienna State Opera, and he also held the post of general music director for the city of Vienna. In 1988, he established the Wien Modern music festival, which flourished and now encompasses other media in addition to music. In 1989, Abbado succeeded von Karajan as music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, remaining in that post until 2002. He gave up his Vienna State Opera post in 1991 but remained active in Vienna. Abbado made recordings with all the major orchestras with which he was associated, and he was prolific even by the standards of the 20th century classical recording golden age. After his death, reissues of his recordings continued to appear, and by the early 2020s, his catalog comprised well over 500 items. Deeply thoughtful in his approach, Abbado was an expert in a wide variety of music, from Mozart to Iannis Xenakis. He often conducted from memory. Abbado cut back his pace after a bout with cancer in 2000 but continued to perform and record, often leading youth orchestras. He died in Bologna, Italy, on January 20, 2014. ~ James Manheim

In most eras, the heavy Verdi, Puccini, and Wagner singers are in the limelight and the smaller-voiced bel canto performers are cast in their shade. This was particularly true in the 1950s and '60s and yet Luigi Alva, unlike so many, never tried to venture out of his natural repertoire, an undertaking usually met with vocal disaster. Instead, he delivered Mozart, Rossini, and Donizetti with great elegance and style for four decades. In his native Peru (home of other noted lyric tenors such as Ernesto Palacio and Juan Diego Florez), he studied in Lima with Rosa Morales and in 1953, continued his studies in Milan with Emilio Ghirardini and Ettore Campogalliani at the La Scuola di Canto at La Scala. Returning to Lima, he made his opera debut in Torroba's zarzuela Luisa Fernandez. He returned to Italy to make his European debut at the Teatro Nuovo in Milan as Alfredo in Verdi's La traviata in 1954, following that with his La Scala debut in 1956 as Count Almaviva in Rossini's The Barber of Seville. Though soprano Maria Callas' few feuds were widely publicized, less-known was her practice of mentoring and encouraging young singers, Alva among them. At Glyndebourne, he made his debut as Nemorino in Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore. His Met debut was in 1964 as Fenton in Verdi's Falstaff. In 1982, he returned to Lima to teach and left the stage in 1989. He sponsors the Luigi Alva Competition for young singers and gives master classes.

Gioachino Rossini's chief legacy remains his extraordinary contribution to the operatic repertoire. His comedic masterpieces, including L'Italiana in Algeri, La gazza ladra, and perhaps his most famous work, Il barbiere di Siviglia, are regarded as cornerstones of the genre along with works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Giuseppe Verdi. He was revered from the time he was a teenager until his death.

Rossini's parents were both working musicians. His father played the horn and taught at the prestigious Accademia Filharmonica in Bologna, and his mother, although not formally trained, was a soprano. Rossini was taught and encouraged at home until he eventually enrolled at the Liceo Musicale in Bologna. After graduation from that institution, the young musician was commissioned by the Venetian Teatro San Moise to compose La cambiale di matrimonio, a comedy in one act. In 1812, Rossini wrote La pietra del paragone, for La Scala theater in Milan and was already, at the tender age of 20, Italy's most prominent composer.

In 1815, Rossini accepted a contract to work for theaters in Naples, where he would remain until 1822, composing prolifically in comfort. He composed 19 operas during his tenure, focusing his attention on opera seria and creating one of his most famous serious works, Otello, for the Teatro San Carlos. While he served in this capacity, Rossini met and courted Isabella Colbran, a local soprano whom he would eventually marry. Other cities, too, clamored for Rossini's works, and it was for Roman audiences that he composed the sparkling comedies Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville, 1816) and La cenerentola (Cinderella, 1817).

In 1822, Rossini left Naples and embarked on a European tour. The Italian musician was received enthusiastically to say the least, and enjoyed fame and acclaim everywhere. Even Beethoven, at the opposite stylistic pole in the musical scene of the day, praised him. The following year, Rossini was commissioned to write Semiramide, a serious opera, for La Fenice, a theater in Venice. This work was less successful in its own day than some of his previous efforts, but spawned several arias that remain part of any vocalist's songbook. In 1824, Rossini traveled via London to Paris where he would live for five years and serve as the music director from 1824 to 1826 at the Théâtre Italien. The composer gained commissions from other opera houses in France, including the Paris Opéra. Rossini composed his final opera, Guillaume Tell (1829), before retiring from composition in that genre at the age of 37. Its overture is not only a concert favorite, but an unmistakable reflection and continuation of Beethoven's heroic ideal. The catalog of work Rossini had written at the time of his retirement included 32 operas, two symphonies, numerous cantatas, and a handful of oratorios and chamber music pieces. After moving back to Italy, Rossini became a widower in 1845. His marriage to Isabella Colbran had not been particularly happy, and shortly after her death, the composer married Olympe Pelissier, a woman who had been his mistress.

In 1855, Rossini, along with his new bride, moved once again, this time settling in Passy, a suburb of Paris. He spent the remaining years of his life writing sacred music as well as delectable miniatures for both piano and voice (some of which he called "sins of my old age"). Rossini was buried in Paris' Père Lachaise cemetery in proximity to the graves of Vincenzo Bellini, Luigi Cherubini, and Frédéric Chopin. In 1887, Rossini's grave was transferred from Paris to Santa Croce, in Florence, in a ceremony attended by more than 6,000 admirers. ~ David Brensilver

Though conventional wisdom would state that no one can serve two masters, piano sensation Giovanni Allevi maintains an impressive career in music and continues to distinguish himself in the field of philosophy. Allevi's charisma and trademark style -- t-shirt, jeans, and sneakers -- have helped him connect to audiences at major venues around the world. He is also an accomplished author.

Born in Ascoli Piceno on April 9, 1969, Allevi first pursued an education in music, earning high marks in piano and composition from the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan. Before entering the professional music world, he graduated cum laude with a PhD in philosophy; his thesis was titled The Emptiness of Modern Physics. Following a stint in the Italian Army Band, Allevi turned his attentions back to composition, releasing 13 Dita (Universal) in 1997. He easily crossed the line between the classical and contemporary music worlds, performing in venues ranging from the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts to New York's famous Blue Note jazz club. Compositions from 13 Dita became well-liked in contemporary piano circles, some of them even performed by Japanese virtuoso Nanae Mimura. Six years later, his second album, Composizioni, was released. In the years that followed, Allevi would perform in key locations throughout the U.S. and Europe, as well as lecture regularly on philosophy and music.

No Concept, released in 2005, garnered Allevi commissions and performance invitations from all corners of the classical music world but also from jazz and contemporary music presenters. While on tour supporting No Concept, Allevi began work on his fourth album, Joy, which would reach his largest audience yet, thanks to a relationship with Sony/BMG. In 2008, Allevi conducted the orchestra I Virtuosi Italiani in his own works as well as those by Puccini for a Christmas concert at the Italian senate, where guests included Italian President Giorgio Napolitano; this concert was broadcast on Italian national television, further raising Allevi's image in the public eye. Allevi's popularity continued to rise through the 2010s through his writing, performances, and recordings. In 2015, he issued the album Love, followed by Equilibrium in 2017 and Hope in 2019. Allevi was the subject of the docuseries Allevi in the Jungle in 2020, and his seventh book, Le regole del pianoforte - 33 note di musica e filosofia per una vita fuori dall’ordinario, was published in 2021.

Allevi received an Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, is an ambassador for Save the Children, and has had an asteroid after him by NASA, giovanniallevi111561. ~ Evan C. Gutierrez & Keith Finke

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?