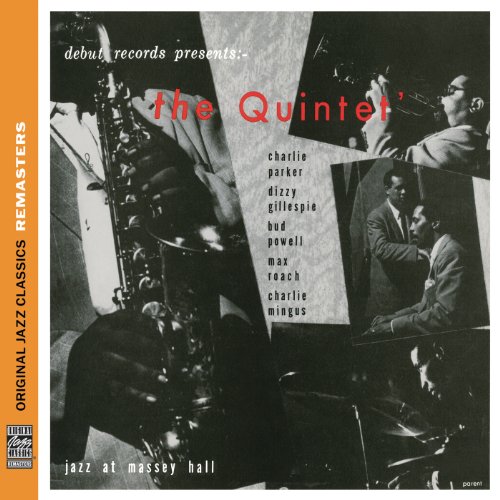

The Quintet: Jazz At Massey Hall [Original Jazz Classics Remasters]

℗© 2012 Concord Music Group, Inc.

Artist bios

Charlie Parker radically reshaped jazz, changing the way musicians, fans and critics approached it. If Dizzy Gillespie was bop's patron saint, Parker was its founding elder. He was an amazing improviser, who used a slow, thin vibrato, astonishing harmonic knowledge and total technical command to recast songs via his solos. He usually ignored the melody and instead went to the harmonic structure. Through breaking the pulse, varying the rhythm, experimenting with pitch, in short, doing any and everything possible, Parker created solos that were fresh, radical and totally distinctive, yet were related to the original and didn't destroy its organization. He knew thousands of tunes, and freely incorporated snatches of Tin Pan Alley, blues, hillbilly, and classical into other tunes. But these weren't randomly inserted; they were included in ways that fit the moment. These snippets were both humorous and relevant. Parker did this while playing at either rapid fire tempos or doing slow, agonizing 12-bar wailers. He emerged as the most imitated, admired saxophonist of his day, and though his influence eventually waned, his impact remains substantial. There aren't many alto saxophonists, especially those playing bebop or related styles, that haven't closely studied his work and committed many Parker solos to memory. He's responsible for numerous American music classics, among them "Confirmation," "Yardbird Suite," "Relaxin' At Camarillo," "Ornithology," "Scrapple From The Apple," "Parker's Mood," and "Now's The Time," which was later reworked into an R&B sensation "The Hucklebuck." Parker got his first music lessons in Kansas City public schools. His father was a vaudevillian. He began playing alto sax in 1931, and worked infrequently before dropping out in 1935 to become a full-time player. Sadly, his involvement with drugs started almost as soon as he began playing professionally. He worked mainly in Kansas City until 1939, playing with jazz and blues groups, and honing his craft in legendary Kansas City jam sessions. One incident during this period stands out; Jo Jones reportedly fired a cymbal at Parker one night in a rage over his playing. His astonishing harmonic skills were developed during this time; Parker eventually was able to modulate from any key to any other key. Local musicians Buster Smith and the great Lester Young were major influences on Parker's early style. Parker initially played with Jay McShann in 1937, and also Harlan Leonard. While in Leonard's band he met Tadd Dameron, a superb arranger. He began developing his lifelong reputation for unpredictability. Parker visited New York in 1939, staying until 1940. He participated in some jam sessions, and was a dishwasher for three months at a club where Art Tatum was playing. He started his harmonic experiments one night at a Harlem club, improvising on the chords upper intervals for "Cherokee" rather than its lower ones. But his first visit to New York didn't make much impact. Parker met Gillespie in 1940, when he came through on tour. He joined McShann's big band in 1940, and remained until 1942. They toured the Southwest, Midwest and in New York, recording in 1941 in Dallas. These were Parker's first sessions. He was beginning to become famous for brillant solos, though still working in strict swing style. There was a short stint with Noble Sissle's band, then he joined Earl Hines in 1942, reuniting with Gillespie. By 1944, he, Gillespie and many other top young players were in Billy Eckstine's big band. Parker had been participating nightly in after hours jam sessions since 1942. These sessions were held at various locations, among them Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House. He began recording after the ban ended in 1944 (though there are some acetates from '43 with Parker on tenor), cutting songs with Tiny Grimes. He began heading his own band in 1945, while working with Gillespie in combos. The two took their group to Hollywood in December of that year, playing a six-week engagement at various clubs. These were historic gigs, with both club audiences and musical lineups a good mix of blacks and whites. Parker remained in Los Angeles, recording for Ross Russell's Dial label and performing until he suffered a nervous breakdown in 1946. His mental and physical (suffering from heroin and alcohol addiction) condition caused him to be confined at the Camarillo State Hospital. After his release in 1947, Parker continued working in Los Angeles, making more fine records for Dial. He came back to New York in April of 1947, forming a quintet with Miles Davis, Duke Jordan, Tommy Potter and Max Roach and cutting several seminal dates. Roy Haynes and Lucky Thompson also worked with this band occasionally, as did Red Rodney and Kenny Dorham. Parker became a larger-than-life celebrity from 1947 to 1951. He played in clubs, did concerts and broadcast performances, toured with Jazz At The Philharmonic, worked in Afro-Latin bands with Gillespie, and visited Europe in 1949 and 1950. He did a controversial session with strings in 1950 that became as popular as anything he ever recorded. At the same time, in the midst of this celebrity status, Parker's drug addiction worsened. He became just as famous for no-shows, pawnshop incidents with his saxophone and irrational behavior as the matchless tone and soaring solos. Parker's cabaret license was revoked in 1951 at the behest of the city's narcotics squad. It was reinstated two years later, but by that time the damage had been done. Parker did appear at the 1953 Massey Hall concert in Canada with Gillespie, Roach, Charles Mingus and Bud Powell, and cut both a wonderful big band release in Washington, D.C. and a combo session at Storyville in Boston that same year. But the end was nearing. Prevented from working in nightclubs, Parker's health steadily declined while his habit grew worse. He twice attemped suicide before committing himself to Bellvue in 1954. His last public appearance came at Birdland, the club named in his honor, in March of 1955. Parker died seven days later, at the Manhattan apartment of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, the same place Thelonious Monk would eventually die. Parker reissues are fortunately widely available. His early work with McShann has been reissued by domestic and import labels. His Verve output has been reissued twice on mammoth sets; once a 10-album box and recently a 10-CD set with many additional tracks. There have been two-record and two-disc best of anthologies. His Dial material has been haphazardly reissued, but there are complete import collections available. Some Prestige material is available, and his landmark Savoy sessions are coming out in separate editions. They've previously been reissued in two-album "best ofs" and complete boxed editions. Hopefully, the handful of Columbia Parker sessions that were available in the '70s on vinyl will reappear. Blue Note has reissued the Storyville session. Elektra had reissued the Washington D.C. date on vinyl, but it was deleted. Mosaic has issued a mammoth boxed set of Parker recordings made by fanatical follower Dean Benedetti, who took a portable recorder to countless Parker performances, concerts and sessions, faithfully copying every Parker solo. This is the only collection in the company's illustrious history they they personally own. Stash has issued the '43 Parker sessions on tenor, and also has issued a two-disc best of Dial package. There's lots of transcription, bootleg and broadcast items available. Ross Russell's self-serving book "Bird Lives!" irritated many by its slant, as did Robert Reisner's "Bird - The Legend Of Charlie Parker." Gary Giddins' "Celebrating Bird - The Triumph Of Charlie Parker" is the best combination of scholarship, commentary and analysis. There are also many accounts available in anthologies. Clint Eastwood valiantly attempted to get Parker's life on the screen with "Bird" in 1988. The results were quite mixed.

Dizzy Gillespie's contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis' emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy's style was successfully recreated. Somehow, Gillespie could make any "wrong" note fit, and harmonically he was ahead of everyone in the 1940s, including Charlie Parker. Unlike Bird, Dizzy was an enthusiastic teacher who wrote down his musical innovations and was eager to explain them to the next generation, thereby insuring that bebop would eventually become the foundation of jazz.

Dizzy Gillespie was also one of the key founders of Afro-Cuban (or Latin) jazz, adding Chano Pozo's conga to his orchestra in 1947, and utilizing complex poly-rhythms early on. The leader of two of the finest big bands in jazz history, Gillespie differed from many in the bop generation by being a masterful showman who could make his music seem both accessible and fun to the audience. With his puffed-out cheeks, bent trumpet (which occurred by accident in the early '50s when a dancer tripped over his horn), and quick wit, Dizzy was a colorful figure to watch. A natural comedian, Gillespie was also a superb scat singer and occasionally played Latin percussion for the fun of it, but it was his trumpet playing and leadership abilities that made him into a jazz giant.

The youngest of nine children, John Birks Gillespie taught himself trombone and then switched to trumpet when he was 12. He grew up in poverty, won a scholarship to an agricultural school (Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina), and then in 1935 dropped out of school to look for work as a musician. Inspired and initially greatly influenced by Roy Eldridge, Gillespie (who soon gained the nickname of "Dizzy") joined Frankie Fairfax's band in Philadelphia. In 1937, he became a member of Teddy Hill's orchestra in a spot formerly filled by Eldridge. Dizzy made his recording debut on Hill's rendition of "King Porter Stomp" and during his short period with the band toured Europe. After freelancing for a year, Gillespie joined Cab Calloway's orchestra (1939-1941), recording frequently with the popular bandleader and taking many short solos that trace his development; "Pickin' the Cabbage" finds Dizzy starting to emerge from Eldridge's shadow. However, Calloway did not care for Gillespie's constant chance-taking, calling his solos "Chinese music." After an incident in 1941 when a spitball was mischievously thrown at Calloway (he accused Gillespie but the culprit was actually Jonah Jones), Dizzy was fired.

By then, Gillespie had already met Charlie Parker, who confirmed the validity of his musical search. During 1941-1943, Dizzy passed through many bands including those led by Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Charlie Barnet, Fess Williams, Les Hite, Claude Hopkins, Lucky Millinder (with whom he recorded in 1942), and even Duke Ellington (for four weeks). Gillespie also contributed several advanced arrangements to such bands as Benny Carter, Jimmy Dorsey, and Woody Herman; the latter advised him to give up his trumpet playing and stick to full-time arranging.

Dizzy ignored the advice, jammed at Minton's Playhouse and Monroe's Uptown House where he tried out his new ideas, and in late 1942 joined Earl Hines' big band. Charlie Parker was hired on tenor and the sadly unrecorded orchestra was the first orchestra to explore early bebop. By then, Gillespie had his style together and he wrote his most famous composition "A Night in Tunisia." When Hines' singer Billy Eckstine went on his own and formed a new bop big band, Diz and Bird (along with Sarah Vaughan) were among the members. Gillespie stayed long enough to record a few numbers with Eckstine in 1944 (most noticeably "Opus X" and "Blowing the Blues Away"). That year he also participated in a pair of Coleman Hawkins-led sessions that are often thought of as the first full-fledged bebop dates, highlighted by Dizzy's composition "Woody'n You."

1945 was the breakthrough year. Dizzy Gillespie, who had led earlier bands on 52nd Street, finally teamed up with Charlie Parker on records. Their recordings of such numbers as "Salt Peanuts," "'Shaw Nuff," "Groovin' High," and "Hot House" confused swing fans who had never heard the advanced music as it was evolving; and Dizzy's rendition of "I Can't Get Started" completely reworked the former Bunny Berigan hit. It would take two years for the often frantic but ultimately logical new style to start catching on as the mainstream of jazz. Gillespie led an unsuccessful big band in 1945 (a Southern tour finished it), and late in the year he traveled with Parker to the West Coast to play a lengthy gig at Billy Berg's club in L.A. Unfortunately, the audiences were not enthusiastic (other than local musicians) and Dizzy (without Parker) soon returned to New York.

The following year, Dizzy Gillespie put together a successful and influential orchestra which survived for nearly four memorable years. "Manteca" became a standard, the exciting "Things to Come" was futuristic, and "Cubana Be/Cubana Bop" featured Chano Pozo. With such sidemen as the future original members of the Modern Jazz Quartet (Milt Jackson, John Lewis, Ray Brown, and Kenny Clarke), James Moody, J.J. Johnson, Yusef Lateef, and even a young John Coltrane, Gillespie's big band was a breeding ground for the new music. Dizzy's beret, goatee, and "bop glasses" helped make him a symbol of the music and its most popular figure. During 1948-1949, nearly every former swing band was trying to play bop, and for a brief period the major record companies tried very hard to turn the music into a fad.

By 1950, the fad had ended and Gillespie was forced, due to economic pressures, to break up his groundbreaking orchestra. He had occasional (and always exciting) reunions with Charlie Parker (including a fabled Massey Hall concert in 1953) up until Bird's death in 1955, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic (where he had opportunities to "battle" the combative Roy Eldridge), headed all-star recording sessions (using Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, and Sonny Stitt on some dates), and led combos that for a time in 1951 also featured Coltrane and Milt Jackson. In 1956, Gillespie was authorized to form a big band and play a tour overseas sponsored by the State Department. It was so successful that more traveling followed, including extensive tours to the Near East, Europe, and South America, and the band survived up to 1958. Among the young sidemen were Lee Morgan, Joe Gordon, Melba Liston, Al Grey, Billy Mitchell, Benny Golson, Ernie Henry, and Wynton Kelly; Quincy Jones (along with Golson and Liston) contributed some of the arrangements. After the orchestra broke up, Gillespie went back to leading small groups, featuring such sidemen in the 1960s as Junior Mance, Leo Wright, Lalo Schifrin, James Moody, and Kenny Barron. He retained his popularity, occasionally headed specially assembled big bands, and was a fixture at jazz festivals. In the early '70s, Gillespie toured with the Giants of Jazz and around that time his trumpet playing began to fade, a gradual decline that would make most of his '80s work quite erratic. However, Dizzy remained a world traveler, an inspiration and teacher to younger players, and during his last couple of years he was the leader of the United Nation Orchestra (featuring Paquito D'Rivera and Arturo Sandoval). He was active up until early 1992.

Dizzy Gillespie's career was very well documented from 1945 on, particularly on Musicraft, Dial, and RCA in the 1940s; Verve in the 1950s; Philips and Limelight in the 1960s; and Pablo in later years. ~ Scott Yanow

One of the giants of the jazz piano, Bud Powell changed the way that virtually all post-swing pianists play their instruments. He did away with the left-hand striding that had been considered essential earlier and used his left hand to state chords on an irregular basis. His right often played speedy single-note lines, essentially transforming Charlie Parker's vocabulary to the piano (although he developed parallel to "Bird").

Tragically, Bud Powell was a seriously ill genius. After being encouraged and tutored to an extent by his friend Thelonious Monk at jam sessions in the early '40s, Powell was with Cootie Williams' orchestra during 1943-1945. In a racial incident, he was beaten on the head by police; Powell never fully recovered and would suffer from bad headaches and mental breakdowns throughout the remainder of his life. Despite this, he recorded some true gems during 1947-1951 for Roost, Blue Note, and Verve, composing such major works as "Dance of the Infidels," "Hallucinations" (also known as "Budo"), "Un Poco Loco," "Bouncing with Bud," and "Tempus Fugit." Even early on, his erratic behavior resulted in lost opportunities (Charlie Parker supposedly told Miles Davis that he would not hire Powell because "he's even crazier than me!"), but Powell's playing during this period was often miraculous.

A breakdown in 1951 and hospitalization that resulted in electroshock treatments weakened him, but Powell was still capable of playing at his best now and then, most notably at the 1953 Massey Hall Concert. Generally in the 1950s his Blue Notes find him in excellent form, while he is much more erratic on his Verve recordings. His warm welcome and lengthy stay in Paris (1959-1964) extended his life a bit, but even here Powell spent part of 1962-1963 in the hospital. He returned to New York in 1964, disappeared after a few concerts, and did not live through 1966.

In later years, Bud Powell's recordings and performances could be so intense as to be scary, but other times he sounded quite sad. However, his influence on jazz (particularly up until the rise of McCoy Tyner and Bill Evans in the 1960s) was very strong and he remains one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time. ~ Scott Yanow

One of the most gifted musicians in jazz history, Max Roach helped establish a new vocabulary for jazz drummers during the bebop era and beyond. He shifted the rhythmic focus from the bass drum to the ride cymbal, a move that gave drummers more freedom. He told a complete story, varying pitch, tuning, patterns, and volume. He was a brilliant brush player, and could push, redirect, or break up the beat. In 1948 he participated in Miles Davis' seminal Birth of the Cool sessions before forming his own quintet with iconic bop trumpeter Clifford Brown. In 1953, he served as drummer in "the quintet" for the historic Jazz at Massey Hall concert, alongside Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Charles Mingus. Later, the drummer's seminal 1961 We Insist! Freedom Now Suite set the tone for Civil Rights activism among his peers. Throughout the 1970s and '80s, Roach continued breaking new ground. He formed the percussion ensemble M'Boom in 1970, issuing a handful of acclaimed albums including 1973's Re: Percussion, M'Boom in 1979, and To the Max in 1991. He worked with vanguard musicians including storied duos with Anthony Braxton (The Long March) and Cecil Taylor (Historic Concerts). During the '90s Roach taught at the University of Massachusetts and continued to perform. He never stood still musically: he worked in trios, with symphony orchestras, backed gospel choirs, and with rapper Fab Five Freddy. Friendship, his final album in collaboration with trumpeter Clark Terry, was issued in 2002.

Roach was born in rural North Carolina in 1924. His mother sang gospel. His family moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, New York in 1928. Roach began his musical vocation as a child playing bugle in parades. He started playing drums at seven, and at ten, he was playing drums in gospel bands. He started playing jazz in earnest while in high school. In 1942, as an 18-year-old graduate, he received a call to fill in for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan. He starting hanging out and sitting in at the jazz clubs on 52nd Street, and at 78th Street & Broadway. His first professional recording took place in December 1943, backing saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. While serving as house drummer at Minton's Playhouse, he fell in with saxophonist Charlie Parker, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and others at the famed locale. He was a frequent participant in after-hours jam sessions. Roach played brief stints with Benny Carter and Duke Ellington's band, then joined Gillespie's quintet in 1943 and served in Parker-led bands in 1945, and from 1947 to 1949. Roach traveled to Paris with Parker in 1949 and recorded there with him and others including Kenny Dorham. He also played with Louis Jordan, Red Allen, and Hawkins. He participated in Miles Davis' historic Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949.

Roach enrolled in a classical percussion degree course at the Manhattan School of Music in 1950. He picked up with Parker again in 1951, and remained with him until he left school in 1953. During that tenure he served as drummer in "the quintet," and played at the historic Jazz at Massey Hall concert in Toronto with Charles Mingus, Bud Powell, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bird. These concerts marked the final time that the latter two would play together. During the early 1950s, Roach also toured with the Jazz at the Philharmonic revue, and recorded with Howard Rumsey's Lighthouse All-Stars, replacing Shelly Manne. During the mid-'50s, he was a sideman with Sonny Rollins for several years and co-led the Max Roach/Clifford Brown orchestra, with Powell's brother Richie on piano and saxophonists Harold Land and later, Rollins. Roach's frenetic, yet precise drumming laid the foundation for Brown's amazing trumpet solos. This group made landmark records during its short tenure, among them Clifford Brown & Max Roach (1954), Study in Brown and Brown and Roach Incorporated (1955), and At Basin Street (1956). Brown and Powell were tragically killed in a car crash on the way to a gig in Chicago in 1956. A devastated Roach tried to keep the group alive with Dorham and Rollins, and later with trumpeter Booker Little and saxophonist George Coleman. He became involved in a record label partnership with Charles Mingus, forming Debut Records in the mid-'50s. The label issued Jazz at Massey Hall in 1958 and Percussion Discussion (considered an avant-garde release at the time). Roach also appeared with Dorham, pianist Ramsey Lewis, saxophonist Hank Mobley, and bassist George Morrow. Later, he led another influential band, this time with Little, Coleman, tuba player Ray Draper, and bassist Art Davis. They cut seminal dates for Riverside and Emarcy, among them Deeds Not Words.

After playing with pianist Randy Weston on Uhuru Afrika, Roach, a deeply committed Civil Rights activist, composed and recorded We Insist! Freedom Now Suite in 1960. A multi-faceted work, it featured vocals by his then-wife Abbey Lincoln and lyrics by Oscar Brown, Jr. It vehemently confronted racial injustice in America, and its influence endures in the 21st century. In 1962, he recorded Money Jungle, a collaborative album with Mingus and Ellington. It is regarded as one of the finest trio albums ever put to tape. Roach and his various bands recorded and toured frequently. He released the collaborative Much Max with Stanley Turrentine in 1964 and the now-classic Drums Unlimited in 1966. In 1968 Roach and the Turrentine Brothers released Let's Groove for Time Records.

In 1970, Roach formed his long-lived percussion ensemble M'Boom. Its original members included Roy Brooks, Warren Smith, Joe Chambers, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, and Freddie Waits. The following year, he led a sextet that included saxophonist Billy Harper, trumpeter Cecil Bridgewater, pianist George Cables, electric bassist Eddie Mathias, and percussionist Ralph MacDonald. This group collaborated with gospel singers J.C. and Dorothy White, Ruby McClure, and a 22-voice choir to record the enduring jazz/gospel fusion outing Lift Every Voice and Sing for Atlantic. The six-track set offered sometimes radical rearrangements of gospel standards arranged by William Bell, Lincoln, and Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson.

Re:Percussion, the debut album by M'Boom, was released by Strata East in 1973 and reissued by Japan's Baystate the following year. Roach continued recording prolifically for various labels. In 1976, he cut the oft-reissued Force - Sweet Mao - Suid Afrika 76 in a duo with saxophonist Archie Shepp, and a year later released The Loadstar for Italy's Horo label, leading a quartet with Harper, Bridgewater, and bassist Reggie Workman. He cut the duo offering Streams of Consciousness with pianist Abdullah Ibrahim in 1977. The drummer's quartet -- with bassist Calvin Hill in place of Workman -- issued Confirmation in 1978, the same year Roach and Anthony Braxton released the duo offering Birth and ReBirth for Black Saint.

In 1980, Columbia released M'Boom. Recorded the previous year, this eponymously titled offering is regarded by critics and historians alike as foundational in the evolution of jazz and world music as it wove together strands from jazz, salsa, African and European traditions. That same year, the drummer's quartet released Pictures in a Frame for Soul Note, and Roach and Shepp recorded and released the double-live duo album The Long March on Switzerland's Hat Hut label, recorded at their concert at the Willisau Jazz Festival. During the same festival, Roach and Braxton played and recorded a duo concert, releasing it as One in Two-Two in One in 1980. In 1981, the Roach quartet, with saxophonist/flutist Odean Pope replacing Harper, issued the charting Chattahoochee Red for Columbia. The following year that group released the historic In the Light, and the drummer issued Swish, a duo with pianist Connie Crothers. In 1984, a December 1979 duo concert between Cecil Taylor and Roach was released as Historic Concerts on Soul Note. That same year, the drummer released Long as You're Living, his Enja debut, with a new quintet including trombonist Julian Priester, Stanley and Tommy Turrentine, and bassist Bobby Boswell, as well as the quartet recordings Scott Free, It's Christmas Again, and Survivors. 1984 also saw the release of Collage, the third album from M'Boom. During that decade, Roach performed with many ensembles, including a group of break dancers and rapper Fab 5 Freddy in what may be the first fusion of jazz and hip-hop.

In 1985 he released Live at Vielharmonie Munich featuring the Swedenborg String Quartet; it was billed to the Max Roach Double Quartet. He followed it that year with Easy Winners in collaboration with the Uptown String Quartet that included his daughter, Maxine Roach, on viola. The string group's name morphed into the Max Roach Double Quartet for 1986's Bright Moments. On June 15, 1989 at La Grande Hale, in La Villette, Paris, Roach took part in the Paris All Stars: Homage to Charlie Parker concert alongside saxophonists Jackie McLean, Phil Woods, and Stan Getz, Gillespie, pianist Hank Jones, bassist Percy Heath and vibraphonist Milt Jackson. The set was released by A&M in 1990 alongside a duo recording with Gillespie simply titled Paris 1989. The year also saw the Manhattan School of Music award Roach -- who had begun teaching full time at University of Massachusetts, Amherst -- an honorary doctorate. He also released Drum Conversation, his first solo percussion album. In 1992, M'Boom issued their final offering, Live at S.O.B.'s for the Blue Moon label.

In 1994, he appeared on Rush drummer Neil Peart's Burning for Buddy, performing "The Drum Also Waltzes" Pt. 1 and Pt. 2 on the first of the two-volume tribute set. Roach spent most of his time teaching, but still performed and discovered new directions in jazz. In 1998, he released Beijing Trio, a collaborative date on the Asian Improv label with pianist Jon Jang and famed erhu player Jiebing Chen. The following year, Explorations ... To the Mth Degree, a duo performance with Mal Waldron from the latter's 1995 70th birthday concert, was released by Slam Productions. In 2002, Roach teamed with longtime friend and trumpeter Clark Terry to release Friendship with bassist Marcus McLaurine and pianist Don Friedman for Columbia. It was the drummer's final album. He became less active due to several forms of illness. Roach died in New York of complications related to Alzheimer's in August 2007. ~ Thom Jurek & Ron Wynn

Bassist, composer, arranger, and bandleader Charles Mingus cut himself a uniquely iconoclastic path through jazz in the middle of the 20th century, creating a musical and cultural legacy that became universally lauded. As an instrumentalist he had few peers -- he was blessed with a powerful tone and pulsating sense of rhythm, capable of elevating the instrument into the frontline of a band. Intensely ambitious yet often earthy in expression, simultaneously politically radical and deeply traditional spiritually, Mingus' music took elements from everything he had experienced -- from gospel and blues, New Orleans jazz, swing, bop, Latin music, modern classical music, and even the jazz avant-garde, and adapted it for ensembles ranging from trios and quartets to sextets and orchestras. His touchstone was the advanced harmonic and timbral swing palette pioneered by Duke Ellington. Mingus took the maestro's harmonic innovations to a different sphere, grafting on gutbucket blues, abrasive dissonances, and introducing abrupt changes in meter and rhythm. While his early works were written out in classical fashion, during the 1950s, influential albums such as Pithecanthropus Erectus, The Clown, and Ah-Um offered a new method of getting his unconventional vision across: he dictated various parts of a composition to his sidemen, all the while allowing room for their individual musical personalities and ideas. This continued throughout the '60s and '70s. His transition from bebop to his pioneering place in hard bop brought to the fore an exciting array of future jazz luminaries including Jackie McLean, Eric Dolphy, Dannie Richmond, and Jimmy Knepper, to mention a few of the musicians he mentored. Mingus was also a formidable pianist, easily capable of playing that role in a group -- which he did in his 1961-1962 bands, hiring another bassist to fill in for him.

Born in a Nogales Army camp, Mingus moved to the Watts district of Los Angeles, where he grew up. The first music he heard was that of the church -- the only music his stepmother allowed around the house -- but one day, despite the threat of punishment, he tuned in to Duke Ellington's "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo" on his father's crystal set, his first exposure to jazz. He tried to learn the trombone at six and then the cello, but became fed up with incompetent teachers and ended up on the double bass by the time he reached high school. His early teachers were Red Callender and an ex-New York Philharmonic bassist named Herman Reinshagen, and he studied composition with Lloyd Reese. A proto-third stream composition written by Mingus in 1940-1941, "Half-Mast Inhibition" (recorded in 1960), reveals an extraordinary timbral imagination for a teenager.

As a bass prodigy, Mingus performed with Kid Ory in Barney Bigard's group in 1942 and went on the road with Louis Armstrong the following year. He would gravitate toward the R&B side of the road later in the '40s, working with the Lionel Hampton band in 1947-1948, backing R&B and jazz performers, and leading ensembles in various idioms under the name Baron Von Mingus. He began to attract real national attention as a bassist for Red Norvo's trio with Tal Farlow in 1950-1951, and after leaving that group, he moved to New York and began working with several stellar jazz performers, including Billy Taylor, Stan Getz, and Art Tatum. He was the bassist in the famous 1953 Massey Hall concert in Toronto with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Max Roach, and he briefly joined his idol Ellington: he had the dubious distinction of being the only man Duke ever personally fired from his band.

Around this time, Mingus tried to make himself a rallying point for the jazz community. He founded Debut Records in partnership with his then-wife Celia and Max Roach in 1952, seeing to it that the label recorded a wide variety of jazz, from bebop to experimental music, until its demise in 1957. Among Debut's most notable releases were the Massey Hall concert, an album by Miles Davis, and several of his own sessions that traced the development of his ideas. He also contributed composed works to the Jazz Composers' Workshop from 1953 to 1955, and in 1955, he founded his own Jazz Workshop repertory group that found him moving away from strict notation toward a looser, dictated manner of composing.

By 1956, with the release of Pithecanthropus Erectus (Atlantic), Mingus had clearly found himself as a composer and leader, creating pulsating, ever-shifting compendiums of jazz's past and present, feeling his way into the free jazz of the future. For the next decade, he would pour forth an extraordinary body of work for several labels, including key albums like The Clown, New Tijuana Moods, Mingus Ah Um, Blues and Roots and Oh Yeah; standards like "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat," "Better Git It in Your Soul," "Haitian Fight Song," and "Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting," and extended works like Meditations on Integration and Epitaph. Through ensembles ranging in size from a quartet to an 11-piece big band, a procession of noted sidemen like Eric Dolphy, Jackie McLean, J.R. Monterose, Jimmy Knepper, Roland Kirk, Booker Ervin, and John Handy would pass, with Mingus' commanding bass and volatile personality pushing his musicians further than some of them might have liked to go. The groups with the great Dolphy (heard live on Mingus at Antibes) in the early '60s might have been his most dynamic, and The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady (1963), is an extended ballet for big band that captures the anguished/joyful split of Mingus' personality in full, and his passionately wild cry.

Mingus felt the lash of racial prejudice intensely -- which, combined with the frustrations of making it in the music business on his own terms, found its outlet in his music; some of his more unique titles were political in nature, such as "Fables of Faubus" (referring to the Arkansas governor who tried to keep Little Rock schools segregated), "Oh Lord, Don't Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me," and "Remember Rockefeller at Attica." But he could also be wildly humorous, the most notorious example being "If Charlie Parker Was a Gunslinger, There'd Be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats" (later shortened to "Gunslinging Bird").

Mingus was almost obsessive in his efforts to free himself from the economic hazards of the music business; so much so that it nearly undermined his sanity during the '60s (some of the liner notes for The Black Saint album were written by his psychologist, Dr. Edmund Pollock). He tried to compete with the Newport festivals by organizing his own Jazz Artists Guild in 1960 that purported to give musicians more control over their work, but that collapsed due to the by-then routine rancor that accompanied so many Mingus ventures, like his calamitous, self-presented New York Town Hall concert in 1962; a shorter-lived recording venture, Charles Mingus Records, in 1964-1965; his failure to find a publisher for his autobiography Beneath the Underdog, and other setbacks that broke his bank account and ultimately his spirit. He quit music almost entirely from 1966 until 1969, resuming performances in June 1969 only because he desperately needed money.

Financial angels in the forms of a Guggenheim Fellowship in composition, the publication of Beneath the Underdog in 1971, and the purchase of his Debut masters by Fantasy boosted Mingus' spirits, and a stimulating new Columbia album, Let My Children Hear Music, thrust him back into public view. By 1974, he had formed a new young quintet anchored by his loyal drummer Dannie Richmond and featuring Jack Walrath, Don Pullen, and George Adams, and more compositions came forth, including the massive, kaleidoscopic, Colombian-based "Cumbia and Jazz Fusion" that began its life as a film score.

Respect for him was growing, but time was running out. In the fall of 1977, Mingus was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease), and by the following year, he was unable to play the bass. Though confined to a wheelchair, he nevertheless carried on, leading recording sessions and receiving honors at a White House concert on June 18, 1978. His last project was a collaboration with folk-rock singer Joni Mitchell, who wrote lyrics to Mingus' music and included samples of Mingus' voice on the record.

Since his death, Mingus' importance and fame have increased exponentially, thanks in large part to the determined efforts of Sue Mingus, his widow. A posthumous repertory group, Mingus Dynasty, was formed almost immediately after his death, and that concept expanded in 1991 into the exciting Mingus Big Band, which resurrected many of Mingus' most challenging scores. Epitaph was finally reconstructed, performed, and recorded in 1989 to general acclaim, and several box sets of portions of Mingus' output have been issued by Rhino/Atlantic, Mosaic, and Fantasy. Beyond re-creations, the Mingus influence can be heard on Branford Marsalis' early Scenes in the City album, and especially in the big-band writing of his brother Wynton. The Mingus blend of wildly colorful eclecticism solidly rooted in jazz history serves his legacy well in a future increasingly populated by young conservatives who want to pay their respects to tradition and try something different.

In the fall of 2018, BBE released the previously unissued archival, multi-disc recording Jazz in Detroit/Strata Concert Gallery/46 Selden. Curator, DJ, and producer Amir Abdullah discovered five two-track master tapes in the care of Hermione Brooks --Â widow of innovative Detroit drummer Roy Brooks, from his time as a member of the Charles Mingus Quintet -- that were recorded live during Mingus' week-long residency in February of 1973. They were broadcast live by drummer/producer and broadcaster Robert "Bud" Spangler on Detroit's public radio station, WDET FM. The Strata Gallery was housed in pianist Kenny and Barbara Cox's multi-purpose home for Strata Records at 46 Selden in what was then known as Cass Corridor. ~ Richard S. Ginell

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?