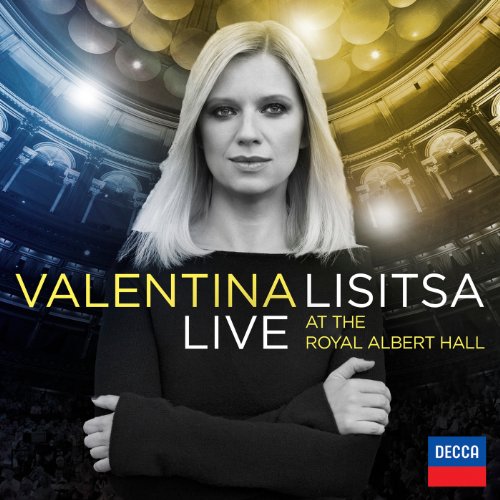

Valentina Lisitsa Live At The Royal Albert Hall

℗© 2012 Decca Music Group Limited

Artist bios

Pianist Valentina Lisitsa was among the first classical musicians to use an internet video service as a significant method of promoting her career. Her strategy was successful: in the 2010s decade she was signed to the major label Decca and has been a fixture in its stable of artists.

Lisitsa was born in Kiev, Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union, on March 25, 1973. She took up the piano at three and was giving concerts within a year, but for a time she hoped to become a professional chess player. Lisitsa attended the Lysenko School of Music in Kiev and then enrolled at the Kiev Conservatory, studying with Ludmilla Tsvierko. There she met pianist Alexei Kuznetsoff, and the pair began performing as duo pianists. They won the Murray Dranoff Two Piano Competition in Miami in 1991 and moved to the U.S., settling in North Carolina. The pair married in 1992. They had some success in the U.S., appearing at the Mostly Mozart Festival in New York in 1995 and making recordings, both as a duo and by Lisitsa as a soloist, on the Audiofon label in the late 1990s. However, Lisitsa's career stalled, and she became interested in the possibilities of new media for promoting classical music. She posted a video on the internet in 2007 and found immediate success in that medium, topping charts in early metrics. Lisitsa hoped that internet stardom would propel her to success in conventional channels of touring and major-label recordings. Her videos did both: in the late 2000s decade she toured the U.S. and Europe as an accompanist to violinist Hilary Hahn. She issued a solo recital of works by Beethoven, Schumann, Liszt, and Sigismond Thalberg on Naxos in 2010, and accompanied Hahn on an Ives sonata recording for Deutsche Grammophon the following year.

In 2010, Lisitsa and Kuznetsoff executed the next step in their plan. They self-financed a recording of the four Rachmaninov piano concertos with the London Symphony Orchestra. This required the investment of their entire life savings, but it paid off. By 2012, with Lisitsa's online views mounting toward the 50 million mark, she was booked at London's Royal Albert Hall and signed to the Decca label. Decca issued her Rachmaninov recordings singly, and she has continued to record for Decca at least yearly. Most of her recordings have focused on Romantic and Russian repertory, but she also issued a recital of music by Philip Glass in 2015. Lisitsa has appeared at top venues including Carnegie Hall and the Royal Albert Hall, but she faced controversy in 2015 as her appearance with the Toronto Symphony was cancelled due to provocative tweets supporting the Russian-backed insurgency in Ukraine (Lisitsa herself is of Russian and Polish ethnic background). In 2019, Lisitsa recorded the complete piano music of Tchaikovsky for Decca.

In mid-2019, a video of her performance of the finale of Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 14 in C sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 2, amassed more than 40 million views. ~ James Manheim

Sergey Rachmaninov was the last, great representative of the Russian Romantic tradition as a composer, but was also a widely and highly celebrated pianist of his time. His piano concertos, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, and his preludes famously test pianists' skills. His Symphony No. 2, the tone poem Isle of the Dead, and his Cello Sonata are also notable. The passionate melodies and rich harmonies of his music have been called the perfect accompaniment for love scenes, but in a greater sense they explore a range of emotions with intense and compelling expression.

Sergey Vasilyevich Rachmaninov, born in Semyonovo, Russia, on April 1, 1873, came from a music-loving, land-owning family; young Sergey's mother fostered the boy's innate talent by giving him his first piano lessons. After a decline in the family fortunes, the Rachmaninovs moved to St. Petersburg, where Sergey studied with Vladimir Delyansky at the Conservatory. As his star continued to rise, Sergey went to the Moscow Conservatory, where he received a sound musical training: piano lessons from the strict disciplinarian Nikolay Zverev and Alexander Siloti (Rachmaninov's cousin), counterpoint with Taneyev, and harmony with Arensky. During his time at the Conservatory, Rachmaninov boarded with Zverev, whose weekly musical Sundays provided the young musician the valuable opportunity to make important contacts and to hear a wide variety of music.

As Rachmaninov's conservatory studies continued, his burgeoning talent came into full flower; he received the personal encouragement of Tchaikovsky, and, a year after earning a degree in piano, took the Conservatory's gold medal in composition for his opera Aleko (1892). Early setbacks in his compositional career -- particularly, the dismal reception of his Symphony No. 1 (1895) -- led to an extended period of depression and self-doubt, which he overcame with the aid of hypnosis. With the resounding success of his Piano Concerto No. 2 (1900-1901), however, his lasting fame as a composer was assured. The first decade of the 20th century proved a productive and happy one for Rachmaninov, who during that time produced such masterpieces as the Symphony No. 2 (1907), the tone poem Isle of the Dead (1907), and the Piano Concerto No. 3 (1909). On May 12, 1902, the composer married his cousin, Natalya Satina.

By the end of the decade, Rachmaninov had embarked on his first American tour, which cemented his fame and popularity in the United States. He continued to make his home in Russia but left permanently following the Revolution in 1917; he thereafter lived in Switzerland and the United States between extensive European and American tours. While his tours included conducting engagements (he was twice offered, and twice refused, leadership of the Boston Symphony Orchestra), it was his astounding pianistic abilities which won him his greatest glory. Rachmaninov was possessed of a keyboard technique marked by precision, clarity, and a singular legato sense. Indeed, the pianist's hands became the stuff of legend. He had an enormous span -- he could, with his left hand, play the chord C-E flat-G-C-G -- and his playing had a characteristic power, which pianists have described as "cosmic" and "overwhelming." He is, for example, credited with the uncanny ability to discern, and articulate profound, mysterious movements in a musical composition which usually remain undetected by the superficial perception of rhythmic structures.

Fortunately for posterity, Rachmaninov recorded much of his own music, including the four piano concerti and what is perhaps his most beloved work, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (1934). He became an American citizen a few weeks before his death in Beverly Hills, CA, on March 28, 1943. ~ Michael Rodman, Patsy Morita

The events of Beethoven's life are the stuff of Romantic legend, evoking images of the solitary creator shaking his fist at Fate and finally overcoming it through a supreme effort of creative will. His compositions, which frequently pushed the boundaries of tradition and startled audiences with their originality and power, are considered by many to be the foundation of 19th century musical principles.

Born in the small German city of Bonn on or around December 16, 1770, he received his early training from his father and other local musicians. As a teenager, he earned some money as an assistant to his teacher, Christian Gottlob Neefe, then was granted half of his father's salary as court musician from the Electorate of Cologne in order to care for his two younger brothers as his father gave in to alcoholism. Beethoven played viola in various orchestras, becoming friends with other players such as Antoine Reicha, Nikolaus Simrock, and Franz Ries, and began taking on composition commissions. As a member of the court chapel orchestra, he was able to travel some and meet members of the nobility, one of whom, Count Ferdinand Waldstein, would become a great friend and patron to him. Beethoven moved to Vienna in 1792 to study with Haydn; despite the prickliness of their relationship, Haydn's concise humor helped form Beethoven's style. His subsequent teachers in composition were Johann Georg Albrechtsberger and Antonio Salieri. In 1794, he began his career in earnest as a pianist and composer, taking advantage whenever he could of the patronage of others. Around 1800, Beethoven began to notice his gradually encroaching deafness. His growing despondency only intensified his antisocial tendencies. However, the Symphony No. 3, "Eroica," of 1803 began a sustained period of groundbreaking creative triumph. In later years, Beethoven was plagued by personal difficulties, including a series of failed romances and a nasty custody battle over a nephew, Karl. Yet after a long period of comparative compositional inactivity lasting from about 1811 to 1817, his creative imagination triumphed once again over his troubles. Beethoven's late works, especially the last five of his 16 string quartets and the last four of his 32 piano sonatas, have an ecstatic quality in which many have found a mystical significance. Beethoven died in Vienna on March 26, 1827.

Beethoven's epochal career is often divided into early, middle, and late periods, represented, respectively, by works based on Classic-period models, by revolutionary pieces that expanded the vocabulary of music, and by compositions written in a unique, highly personal musical language incorporating elements of contrapuntal and variation writing while approaching large-scale forms with complete freedom. Though certainly subject to debate, these divisions point to the immense depth and multifariousness of Beethoven's creative personality. Beethoven profoundly transformed every genre he touched, and the music of the 19th century seems to grow from his compositions as if from a chrysalis. A formidable pianist, he moved the piano sonata from the drawing room to the concert hall with such ambitious and virtuosic middle-period works as the "Waldstein" (No. 21) and "Appassionata" (No. 23) sonatas. His song cycle An die ferne Geliebte of 1816 set the pattern for similar cycles by all the Romantic song composers, from Schubert to Wolf. The Romantic tradition of descriptive or "program" music began with Beethoven's "Pastoral" Symphony No. 6. Even in the second half of the 19th century, Beethoven still directly inspired both conservatives (such as Brahms, who, like Beethoven, fundamentally stayed within the confines of Classical form) and radicals (such as Wagner, who viewed the Ninth Symphony as a harbinger of his own vision of a total art work, integrating vocal and instrumental music with the other arts). In many ways revolutionary, Beethoven's music remains universally appealing because of its characteristic humanism and dramatic power. ~ Rovi Staff

Liszt was the only contemporary whose music Richard Wagner gratefully acknowledged as an influence upon his own. His lasting fame was an alchemy of extraordinary digital ability -- the greatest in the history of keyboard playing -- an unmatched instinct for showmanship, and one of the most progressive musical imaginations of his time. Hailed by some as a visionary, reviled by others as a symbol of empty Romantic excess, Franz Liszt wrote his name across music history in a truly inimitable manner.

From his youth, Liszt demonstrated a natural facility at the keyboard that placed him among the top performing prodigies of his day. Though contemporary accounts describe his improvisational skill as dazzling, his talent as a composer emerged only in his adulthood. Still, he was at the age of eleven the youngest contributor to publisher Anton Diabelli's famous variation commissioning project, best remembered as the inspiration for Beethoven's final piano masterpiece. An oft-repeated anecdote -- first recounted by Liszt himself decades later, and possibly fanciful -- has Beethoven attending a recital given by the youngster and bestowing a kiss of benediction upon him.

Though already a veteran of the stage by his teens, Liszt recognized the necessity of further musical tuition. He studied for a time with Czerny and Salieri in Vienna, and later sought acceptance to the Paris Conservatory. When he was turned down there -- foreigners were not then admitted -- he instead studied privately with Anton Reicha. Ultimately, his Hungarian origins proved a great asset to his career, enhancing his aura of mystery and exoticism and inspiring an extensive body of works, none more famous than the Hungarian Rhapsodies (1846-1885).

Liszt soon became a prominent figure in Parisian society, his romantic entanglements providing much material for gossip. Still, not even the juiciest accounts of his amorous exploits could compete with the stories about his wizardry at the keyboard. Inspired by the superhuman technique -- and, indeed, diabolical stage presence -- of the violinist Paganini, Liszt set out to translate these qualities to the piano. As his career as a touring performer, conductor, and teacher burgeoned, he began to devote an increasing amount of time to composition. He wrote most of his hundreds of original piano works for his own use; accordingly, they are frequently characterized by technical demands that push performers -- and in Liszt's own day, the instrument itself -- to their limits. The "transcendence" of his Transcendental Etudes (1851), for example, is not a reference to the writings of Emerson and Thoreau, but an indication of the works' level of difficulty. Liszt was well into his thirties before he mastered the rudiments of orchestration -- works like the Piano Concerto No. 1 (1849) were orchestrated by talented students -- but made up for lost time in the production of two "literary" symphonies (Faust, 1854-1857, and Dante, 1855-1856) and a series of orchestral essays (including Les préludes, 1848-1854) that marks the genesis of the tone poem as a distinct genre.

After a lifetime of near-constant sensation, Liszt settled down somewhat in his later years. In his final decade he joined the Catholic Church and devoted much of his creative effort to the production of sacred works. The complexion of his music darkened; the flash that had characterized his previous efforts gave way to a peculiar introspection, manifested in strikingly original, forward-looking efforts like Nuages gris (1881). Liszt died in Bayreuth, Germany, on July 31, 1886, having outlived Wagner, his son-in-law and greatest creative beneficiary.

Frédéric Chopin was the most famous composer of Polish origin in the history of Western concert music. He was a progressive who revolutionized the harmonic content, the texture, and the emotional quality of the small piano piece, turning light dance forms, nocturnes, and study genres into profound works that were both daring and deeply inward.

Born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin to a French father and a Polish mother, probably on March 1, 1810, he was a native of Zelazowa Wola village west of Warsaw. In these rustic surroundings, he was exposed to both the classics of keyboard music (including, significantly, those of Bach), by teachers who immediately recognized him as a prodigy, and to Polish folk music, which would be reflected in a pioneering musical nationalism. He quickly outstripped the talents of most of Warsaw's top piano and composition teachers, and when he graduated from the Main School of Music in 1829, professor Józef Elsner pronounced him a genius. That year, Chopin set out on a tour of Austria, Germany, and France. During this period, he wrote his two piano concertos, which contain much of the typical brilliant style of virtuoso piano music of the era, but show the development of a gift for distinctive melody, both ornate and emotionally deep. Chopin returned to Warsaw but departed again, first for Vienna, where he heard news that Poland's uprising against its Russian, Prussian, and Austrian rulers had failed. The Polish national spirit would pervade some of his larger works, including the so-called "Revolutionary" Etude (the Etude in C minor, Op. 10, No. 12). He was encouraged by composer Robert Schumann, who reviewed his Variations, Op. 2, with the words "Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!"

In 1832, Chopin headed for Paris, in many ways the center of European cultural life, and dazzled the city's musical elite, including Franz Liszt, in a concert at the Salle Pleyel. He immediately found himself in demand as a piano teacher, and soon he decided to settle in Paris, although he always hoped to return to Poland. He performed at aristocratic salons, cultivating then-new genres such as the étude (the word means "study," but in Chopin's hands it became much more), the nocturne, the waltz, and, in a Polish vein, the mazurka and the polonaise. After a planned marriage to a Polish girl, Maria Wodzinska, fell through, Chopin met writer Aurore Dudevant, who used the pen name George Sand. The pair began a torrid affair (Sand was married) and traveled together in 1838 to Mallorca, Spain, where they found the local citizenry disapproving of their unconventional relationship and were forced to lodge in a disused monastery. Chopin's creativity was fired, and he would write brilliantly innovative sets of piano music over the next few years. However, the weather turned cold in the winter of 1838-1839, and Chopin's health worsened as he and Sand lived in the unheated building; he was probably already suffering from tuberculosis. Back in France, Chopin and Sand took up residence in Paris and in summers at her estate in Nohant, where Chopin composed prolifically and the couple hosted painter Eugène Delacroix and other members of the cream of French artistic society. The romance cooled, though, and finally ended in 1847. One factor precipitating the breakup was Sand's negative portrayal of Chopin in her 1846 novel Lucrezia Floriani.

Chopin's health was also worsening badly; he found it difficult to perform and could no longer attract crowds as a virtuoso. During political unrest in Paris in 1848, Chopin fled to the British Isles. He performed in London (once for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert) and in Glasgow, where he was the subject of romantic interest from Scots noblewoman Jane Stirling. Chopin, however, remarked that he was "closer to the grave than the nuptial bed," and indeed in November of 1848 he gave what would be his last concert, for Polish refugees. He returned to Paris and continued to receive a steady stream of admirers despite what was clearly a terminal illness; singer Pauline Viardot, according to historians Kornel Michałowski and Jim Samson, remarked that "all the grand Parisian ladies considered it de rigueur to faint in his room." Chopin died in Paris on October 17, 1849. ~ James Manheim

Mystic, visionary, virtuoso, and composer, Scriabin dedicated his life to creating musical works which would, as he believed, open the portals of the spiritual world. Scriabin took piano lessons as a child, joining, in 1884, Nikolay Zverov's class, where Rachmaninov was a fellow student. From 1888 to 1892, Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory, where his teachers included Arensky, Taneyev, and Safonov. Although Scriabin's hand could not easily stretch beyond an octave, he developed into a prodigious pianist, launching an international concert career in 1894. Scriabin started composing during his Conservatory years. Mostly inspired by Chopin, his early works include nocturnes, mazurkas, preludes, and etudes for piano. Typical examples of Romantic music for the piano, these works nevertheless reveal the composer's strong individuality. Toward the end of the century, Scriabin started writing orchestral works, earning a solid reputation as a composer, and obtaining a professorship at the Moscow Conservatory in 1898. In 1903, however, Scriabin abandoned his wife and their four children and embarked on a European journey with a young admirer, Tatyana Schloezer. During his sojourn in Western Europe, which lasted six years, Scriabin started developing an original, highly personal musical idiom, experimenting with new harmonic structures and searching for new sonorities. Among the works composed during this time was the Divine Poem.

In 1905, Scriabin discovered the theosophical teachings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, which became the intellectual foundation of his musical and philosophical efforts. In true Romantic tradition, he sought to situate his work as a composer in the wider spiritual and intellectual context of his age. Previously influenced by Nietzsche's ideas about the advent of a superhuman being, Scriabin embraced theosophy as an intellectual framework for his profound feelings about humankind's quest for God. Works from this period, exemplified by the Poem of Ecstasy (1908) and Prometheus (1910), reflect Scriabin's conception of music as a bridge to mystical ecstasy. While the ideas underlying his works may seem far-fetched, Scriabin's musical language included some fascinating, and very tangible, innovations, such as chords based on fourths and unexpected chromatic effects. Lacking an inner forward-moving force, Scriabin's later works nevertheless fascinate the listener by harmonic transformations which aim to reflect certain undefinable aspects of human consciousness. In addition, the composer, who strongly believed in the synaesthetic nature of art, experimented with sounds and colors, indicating, for example, lighting specification for the performance of particular works. Indeed, Scriabin's interest in color was hardly academic, considering that , as an orchestrator, he exploited the full potential of orchestral color. While Scriabin never quite crossed the threshold to atonality, his music nevertheless replaced the traditional concept of tonality by an intricate system of chords, some of which (e.g., the "mystic chord": C-F sharp-B flat-E-A-D) had an esoteric meaning. Scriabin's gradual move into realms beyond traditional tonality can be clearly heard in his ten piano sonatas; the last five, composed during 1912-1913, are without key signatures and certainly contain atonal moments. In 1915, Scriabin died in of septicemia caused by a carbuncle on his lip. Among his unfinished project was Mysterium, a grandiose religious synthesis of all arts which would herald the birth of a new world.

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?