Verdi: Il trovatore (Live)

ÔäŚ┬ę 2014: Walhall Eternity Series

Artist bios

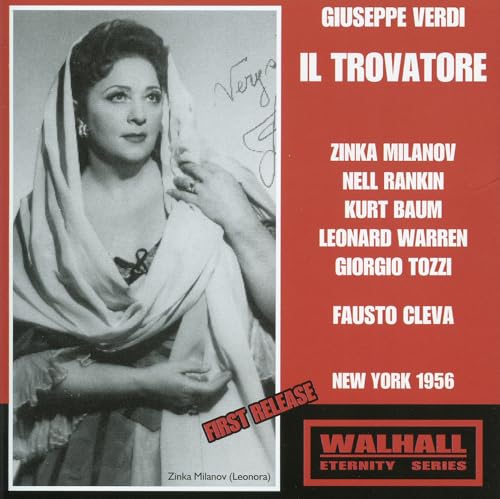

Zinka Milanov was a Croatian soprano who was one of the most famous personalities in opera throughout her career. Specializing in the "spinto" repertoire of Verdi, Puccini, and Bellini, her voice was often described as being powerful and lush with translucent beauty. She was born into a musical family in Zagreb on May 17, 1906. Her father was a bandmaster, her brother was a composer and pianist, and her uncle was also a composer who wrote several songs for her. She sang throughout her childhood and in 1920 she enrolled at the Zagreb Music Academy and studied voice with Milka Ternina, the acclaimed Wagner specialist. One year later, she performed her first recital in her hometown, and in 1927 she performed the part of Leonora in Verdi's Il Travatore as her operatic debut. The following season, she performed the same role in a debut performance with the Dresden Opera. However, her very displeased vocal instructor Ternina also heard this performance and continued working with Milanov on her technique. Later, she also studied with Maria Kostren─Źi─ç, Fernando Carpi, and Jacques St├╝ckgold. Over the next six years, she sang as the lead soprano with the Zagreb Opera and performed throughout Europe. In 1936, she performed in a production of Aida conducted by Bruno Walter in Vienna. Walter was so impressed with her voice that he recommended her to Toscanini, who needed a soprano for his performance of the Verdi Requiem for the 1937 Salzburg Festival. Although Toscanini was not initially happy with her phrasing and musicianship, the performance was a success. Three months later in December 1937 she made her New York debut with the Metropolitan Opera, beginning a long association that lasted until 1966 and included 424 performances. Throughout the 1940s, she made several recordings and sang in Buenos Aires, San Francisco, and Chicago, but due to the circumstances of World War II, she didn't return to Europe until her 1950 debut at La Scala. In 1966, she gave her final performance at the Metropolitan Opera House, and gradually transitioned to the life of an educator. Eleven years after her retirement from performing, she joined the faculty at the Curtis Institute of Music and fulfilled her sense of duty to pass on her knowledge and artistry. She passed away at Lennox Hill Hospital in Manhattan on May 30, 1989, after suffering a stroke. ~ RJ Lambert

A dramatic tenor alternately gauche and exciting, Kurt Baum filled a crucial spot for the Metropolitan Opera and other houses without ever quite having attained star status. Long after his nominal retirement from the stage, he continued to make concert appearances. Noted throughout his career for stentorian top notes, he later wrote several treatises on preservation of the voice and singing well in old age. Whatever his deficiencies as an artist, he was an exemplar of longevity. That he could apply himself to artistic high purpose can be heard on a Traubel/Melchior disc of Wagner in an extended scene from Lohengrin. Urged by his businessman father to become a doctor, Baum spent his high school and college years in Cologne, Germany, before entering medical school at Prague University in 1927. During this period, Baum engaged in a number of athletic activities, becoming the amateur boxing champion of Czechoslovakia. He also evinced a strong interest in music. According to one story -- perhaps true, perhaps not -- his singing voice gained in timbre and strength when his nose was broken by famous German boxer Max Schmeling (there may have been some truth to the event having taken place, but Baum was noted for having a tight vocal production from the very beginning of his career). Urged by friends to sing professionally, Baum left medical school and enrolled at Berlin's Music Academy in 1930. By 1933, Baum was sufficiently well prepared to win the Vienna International Singing Competition, taking first prize among 700 contestants. Heard by the Intendant of the Zurich Opera, Baum was engaged for that company and made his debut there in 1933 singing in Alexander von Zemlinsky's Der Kreidekreis. After singing a variety of lyric roles at Zurich, Baum was engaged the following year by the Deutsches Theater for a succession of more dramatic roles. Feeling the need for further study, Baum traveled to Italy to work with Eduardo Garbin in Milan and with faculty at Rome's Accademia Santa Cecilia. Fortified with additional technical expertise, Baum sang in many of Europe's leading houses in Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Monte Carlo, and at Salzburg. Heard in Monte Carlo by the director of the Chicago Opera, Baum was engaged and made his American debut in Chicago on November 2, 1939, singing Radames to the Aida of Rose Bampton. He was heard in subsequent seasons as Don Jos├ę and Manrico. Meanwhile, Baum joined the Metropolitan Opera, making his debut on November 27, 1941, as the Italian Singer in Der Rosenkavalier. In this short but memorable part, his talents were well matched to the role's requirements. Critic Robert Lawrence described his singing as being of "excellent quality," noting the power of his top notes. For the next quarter century, Baum sang the spinto repertory at the Metropolitan to reviews both complimentary and critical. When the company mounted Wozzeck for the first time in 1959, Baum found a highly congenial role in the preening Drum Major. After WWII, Baum returned to Europe and made his debut at La Scala as Manrico and re-established relations with several other major companies. He appeared for the first time in London, where he was found to be a "rather metallic" Radames in his June 4, 1953, debut. During the 1956 -- 1957 season, he was booed as Manrico. Several early Maria Callas recordings made live in Mexico City show Baum at his best -- and worst.

Warren had a remarkably well-produced voice, with a naturally wide range, with secure high notes, and smooth, rich timbre throughout. He was most associated with Verdi, which he sang with a good deal of artistry and feel for the natural line, though he also excelled in Puccini (especially Scarpia) and verismo.

He first planned on a business career, and studied for a year at Columbia College, but in 1933 decided to quit that to pursue a singing career. He first studied at the Greenwich House Music School, and in 1935, auditioned at the Radio City Music Hall. He had hoped to become a lead singer, but Robert Weede was the reigning baritone there, and Warren was just offered a place in the choir. He sang there for the next three years, augmenting his income with the occasional radio program, wedding, or funeral, and studied with Sidney Dietch, and eventually made it to the Metropolitan Auditions of the Air in 1938. When the Radio City Music Hall refused his request for a few weeks off to prepare (he knew only a few arias and had never sung on the opera stage before), he quit, and threw himself into preparations on his own. Legend has it that at the audition, the conductor Wilfred Pelletier rushed backstage, convinced that they were playing a prank on him, and Warren was lip-synching to a Ruffo or De Luca recording.

He won, rather to his own surprise, not only the auditions but a stipend to study in Italy with, among others, Giuseppe de Luca and Riccardo Picozzi. There, he learned five complete roles in less than seven months, despite having seen just one complete opera in his life. He made his Met debut, which was also his staged opera debut, as Paolo in Verdi's Simon Boccanegra in January of 1939 (Tibbett sang Boccanegra), and soon became a favorite baritone at that house, singing all the major Verdi baritone roles. At first awkward on stage, he studied acting, and while never a great operatic actor, became more at ease on stage and put a good deal of thought into his interpretations. Like many opera stars of the time he was offered film contracts, and made his film debut in 1949 in When Irish Eyes are Smiling. He created the role of Ilo in Menotti's The Island God (which Menotti withdrew shortly after the premier). Like his successor, Robert Merrill, and to a lesser extent Sherrill Milnes, as well as his predecessor, Lawrence Tibbett, his artistic home was the Met, though he did perform in other countries, making his Teatro Colon debut as Rigoletto in 1942, appearing in Il Trovatore in Mexico City in 1948, and making his La Scala debut in 1953 as Iago. In 1958, he also made a tour of the Soviet Union. He had been suffering from high blood pressure, and died on stage at the Metropolitan during a 1960 performance of La Forza del Destino.

His Macbeth under Erich Leinsdorf, with Leonie Rysanek (BMG/RCA GD 84516), is excellent, and he and Bjoerling are both at their best on a recording, also with Leinsdorf, of Tosca (BMG/RCA GD 84514), though Milanov's vocal difficulties are something of an impediment to the complete success of the recording. ~ Ann Feeney

Regarded as a useful house conductor during his many years at the Metropolitan Opera, Fausto Cleva died before he saw his reputation grow to the more generous assessment that prevailed decades later. Always known as a singer's maestro, Cleva was also a conscientious interpreter of bracing urgency, a shrewd mentor, and an individual of integrity. Cleva's studies began at the conservatory in his native Trieste and continued in Milan. Shortly after he had made his debut at Milan's Teatro Carcano in 1920 conducting La traviata, Cleva traveled to America, almost immediately beginning his long association with the Metropolitan Opera. Serving as an assistant conductor from 1920 to 1925, and again from 1938 to 1940 (he served two stints as chorus master, as well, from 1935 to 1938 and in 1940 and 1941), he waited until February 14, 1942, to be assigned a performance of Rossini's Il barbi├Ęre di Siviglia. Although reviews were laudatory, further opportunities seemed too doubtful to keep him in New York. Cleva departed to attend to other engagements, most notably at the Cincinnati Summer Opera, where he served as music director from 1934 to 1963. Other major American companies welcomed him as well. He conducted in Chicago (where he led performances from 1942 until the demise of the Chicago Opera in 1946, receiving especially good reviews for his leadership of the 1944 opening-night Carmen) and in San Francisco, strengthening that conducting roster beginning with a 1942 La traviata with Bid├║ Say├úo. His position in the Italian wing of the San Francisco Opera substantially grew in the early '50s until his return to the Metropolitan as a full-fledged conductor expanded to keep him largely in New York. Cleva's November 13 direction of the Aida that opened the 1951 - 1952 Metropolitan season was regarded as the most sharply realized to have been heard in years, strongly cast with Milanov, del Monaco, and London. Concentrating on the Italian repertory with frequent excursions into the French, Cleva amassed a total of 677 Metropolitan Opera performances before his death while leading an Athens outdoor performance of Gluck's Orfeo et Euridice in 1971. Among Cleva's too-few recordings, a sumptuously cast Luisa Miller is a worthy memento of an underrated conductor.

The Chorus of the Metropolitan Opera has been instrumental in the establishment and continuation of excellence that has marked the Met as one of the premier opera houses in the world. With a flexible roster of professional singers, the Chorus is able to adapt to meet the demands of one of the integral parts of opera performance since the genre's birth. With the Met's continued outreach and ability to incorporate new media, the Chorus has been heard on hundreds of recordings and seen by audiences around the world on video, including a groundbreaking live-broadcast stream to movie theaters.

The Metropolitan Opera was founded in 1883 after an effort led by New York's Roosevelt, Morgan, and Vanderbilt families to establish a world-class company. Right from the start, the new company was a success, and its Orchestra and Chorus have remained vital to its mission. Auguste Vianesi was the company's first music director, and a long list of notable names have followed, including Arturo Toscanini, Bruno Walter, and James Levine, among many others. The role of chorus master of the Metropolitan Opera Chorus has also been held by a distinguished list, most notably Kurt Adler, who held this title, as well as that of principal conductor for a time, from 1943 until 1973.

The Metropolitan Opera has been on the leading edge of technology practically since its founding. In the first years of the 20th century, around 140 recordings of the Met were made on phonograph cylinders, named the Mapleson Cylinders, between 1901 and 1903. In 1910, the company began broadcasting, with live performances transmitted to a relatively nearby area. However, in the 1930s, these live productions were broadcast nationally by several major networks and eventually by the Met itself on its Metropolitan Opera Radio Network. Similarly, with the advent and wider preponderance of television, the Met began broadcasting live performances to households in the 1940s while also dabbling in distributions to movie theaters. These traditions have continued and evolved with technology and, as of the early 2020s, include live performances simulcast in high definition to movie theaters, taped performances broadcast on television, a dedicated streaming radio station, and a litany of well-regarded recordings. Yannick N├ęzet-S├ęguin has served as the Met's music director since 2018, and as of 2023, Donald Palumbo held the title of chorus master. ~ Keith Finke

New York's Metropolitan Opera Orchestra dates back as an established ensemble almost to the Metropolitan Opera's founding in the 1880s. The orchestra has been led by legendary conductors of the 20th and 21st centuries, including Arturo Toscanini, George Szell, and James Levine.

New York upper-crust families launched an effort to establish a world-class opera company in 1880, and the Metropolitan Opera was launched with the 1883-1884 season. August Vianesia was the music director but was soon replaced in 1886 by Anton Seidl, a prot├ęg├ę of Wagner who molded the orchestra into a first-class group along German lines before departing in 1897. Other important early conductors included Alfred Hertz, Gustav Mahler (1908-1910), and Toscanini, who headed the orchestra from 1908 to 1915. Orchestra members by the 1930s earned starting salaries of some $10,000, less than the superstar singers the company engaged but more than what most other orchestras paid, and ever since then, a seat in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra has been a plum assignment for orchestral musicians.

Through the middle of the 20th century and beyond, the Metropolitan Opera was led by European-born conductors who were also prominent in the field of orchestral music, including Szell, Bruno Walter (1941-1951), Fritz Reiner, Erich Leinsdorf, and Dmitri Mitropoulos. The company pioneered operatic broadcasts on radio (from 1930) and television (from 1940), which arguably increased the prominence of the orchestra since audiences experienced no visual component; broadcasts, now including those via the Internet, have remained important to the Met's mission. Doubtless, the most significant of the orchestra's more recent conductors has been James Levine, whose career ended under a cloud but who shaped bold interpretations, many of them in part orchestrally based, for decades. Levine was succeeded by Fabio Luisi and by Yannick N├ęzet-S├ęguin, music director since 2018. The orchestra has issued several recordings independent of operatic productions, including one of Wagner's orchestral music and, in 2022, A Concert for Ukraine. ~ James Manheim

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?