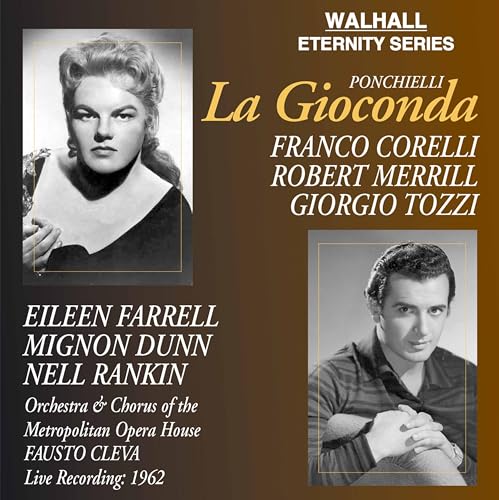

La Gioconda

℗© 2021: Walhall Eternity Series

Artist bios

While opera singers who dabble in popular music are common, those who do so successfully are rare, and those with large dramatic voices who do so are rarer still. Eileen Farrell was as authentic and natural a blues and jazz singer as she was an operatic soprano. She was in fact much more comfortable on the concert stage, on radio, and in the recording studio than in the opera house. She sang relatively few fully-staged performances and was ambivalent about opera and particularly opera house management throughout her entire career (when she taught at Indiana University, she hung a sign outside her office that read, "Help stamp out opera.") Her voice was huge, but capable of great nuances in volume and expressiveness as well as rapid and accurate coloratura, letting her sing bel canto roles such as Cherubini's Medea, the spinto-coloratura Leonora in Verdi's Il trovatore, the verismo Santuzza in Cavalleria Rusticana, and the great Wagner parts of Isolde and Brünnhilde (in concert).

Her parents were both singers, The Singing O'Farrells, and recognizing her potential, sent her to study voice in New York. She auditioned for various radio shows and was hired by CBS for chorus and ensemble work. In 1941, she got her own program, Eileen Farrell Sings, where she performed songs and lighter classical music. She remained with them until 1947, when she began to explore other venues, including the Bach Aria Group. She also began studying with Eleanor McLellan, who helped her hone her vocal technique, particularly helping her develop a pianissimo. In 1955, she sang for the film dramatization of singer Marjorie Lawrence's life, Interrupted Melody (Eleanor Parker acted the role), and the music, ranging from folk to Brünnhilde's immolation scene, showed off her power, rich voice, and versatility. In 1957, she appeared for the first time on the opera stage, as Santuzza in Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana in Tampa, FL, and two years later, sang for the first time in London, in a recital. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1960 in the title role of Gluck's Alceste, and in 1962, won a Grammy for her recording of Wagner's Wesendonck Lieder and the "Immolation Scene" from Götterdämmerung, conducted by Leonard Bernstein. Her relationship with Met management was an uncomfortable one, partly due to differences of personalities and her finding the repertoire they offered unchallenging, and her contract was allowed to drop in 1965. Towards the end of the decade, her voice was beginning to show signs of wear at the very top, and Farrell moved back into jazz and blues recordings, and taught music at Indiana University. She made her last record in 1993, at the age of 72. Farrell died on March 23, 2002.

"Thrilling" is the word that inevitably seems to come up in discussion of Franco Corelli, whether in reference to his powerful, immediately identifiable voice or his matinee idol good looks. (He was one of the few tenors whose appearance was actually enhanced by Renaissance style tights, and after one such appearance was nicknamed "The Golden Calves.") While he was no stylist, or rather, sang everything "Corelli style," altering rhythms to suit his voice, inserting or prolonging high notes whenever he felt like it, and almost never displaying a high level of finesse, nuance, or sensivitiy to phrasing, for his admirers, he was the quintessence of operatic excitement.

Rather unusually, he did not come from a musical family, discovered his own talent relatively late in life, and was almost completely self taught. He had studied for an engineering career, but friends encouraged him to think about music, and he briefly studied at the Pesaro Conservatory when he was in his early twenties. In 1951, he won the Maggio Musicale competition, but decided to discontinue formal musical studies shortly afterwards. Instead, he spent his time listening to recordings of great tenors of the past, particularly Caruso, Gigli, and Lauri-Volpi, in the repertoire which he himself hoped to sing. He made his operatic debut as Don Jose in a production of Carmen in Spoleto, also during 1951.

Despite not having the network of teachers that many students have, he quickly grew in reputation, appeared in a television production of Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, and made his La Scala debut in Spontini's La Vestale as Licinio, in 1954. His Covent Garden debut in 1957 was as Cavaradossi in Puccini's Tosca, and his Metropolitan Opera debut as Manrico in 1961. While he had a definite "bleat" in his voice during his early years that led to some critics dubbing him "PeCorelli" (Italian for "goat"), he did learn to overcome that, and also to add a ravishing pianissimo to his singing, though his phrasing remained more or less crude. Over the coming years, La Scala and the Met were the houses where he appeared most frequently. He constantly suffered from stage fright, and many of his divo antics, offstage and on, might have stemmed from that, but on stage, he cut a dashing figure, though somewhat more inclined to pose than to act. In one memorable staging of Don Carlo, feeling that Boris Christoff, the bass singing King Philip was getting too much audience attention, he provoked a genuine sword fight with the no less feisty Christoff during the auto-da-fe scene, until a brave supernumerary (spear carrier) physically separated the two. In yet another staging of the same scene and opera, he didn't come out onto the stage until long after his cue; he had been in the middle of a dispute backstage, and wanted to win that before he came out to sing.

He sang a wide variety of roles from the Italian and French repertoire, including several works that had been relative obscurities, such as Meyerbeer's Les Hugenots and Donizetti's Poliuto. Appropriately, considering how he learned to sing, he made several recordings, mostly for EMI/Angel. Among the recordings that capture him at his best are an Andrea Chenier, conducted by Santini (EMI CDS5 65287-2) and a selection of arias and songs (EMI Double Forte CZS 569530 2.) ~ Ann Feeney

American baritone Robert Merrill, born Moishe Miller in Brooklyn on June 4, 1917, wavered -- in genuine New Yorker fashion -- between a professional baseball career and one in opera before being pushed into vocal studies by his mother. During an intensive period of study with vocal coach Samuel Margoles, Merrill worked as a pop singer at a Catskills resort to gain experience; he occasionally included the famous "Largo al factotum" from Rossini's Il Barbiere di Siviglia in his programs, earning great applause. Undiscouraged by his failure to win his first Metropolitan Opera audition, he continued to sing; two years later, auditions director Wilfrid Pelletier asked him to try again. This time he was ready; as a winner of the Metropolitan Auditions of the Air, he made his Metropolitan Opera debut on December 15, 1945, as Germont père in La Traviata, opposite the Violetta of Licia Albanese and Richard Tucker's Alfredo. It was a role he was also privileged to sing under Arturo Toscanini.

Despite immediate audience popularity and the enthusiasm of Met management, Merrill pursued his career cautiously, staying with less demanding parts -- Renato in Un Ballo in maschera, Rodrigo in Don Carlo, Valentin in Faust, and Marcello in La bohème -- until he felt prepared for such larger roles as the Count di Luna in Il Trovatore, Barnaba in La Gioconda, Amonasro in Aida, and, eventually, Iago in Verdi's Otello. Large or small, nearly everything he sang made an indelible impression. For instance, his Marcello for Sir Thomas Beecham's 1956 recording of La bohème, with de los Angeles and Björling, brings interest and character to a part often eclipsed by the principals. Gradually, his repertory broadened to include some 20 roles, and over a career of 30 years, he was heard at the Met 750 times. Merrill's most notable foreign appearances were both as the elder Germont (a mainstay) -- in Venice in 1961, and at London's Covent Garden in 1967.

Escamillo, in Carmen, has been one of Merrill's most spectacular characterizations -- one which, at the Met, he came to own, so to speak; he recorded the role in 1959 opposite the legendary Carmen of Risë Stevens, with Jan Peerce as Don José. Fritz Reiner conducted. Five years later he repeated his triumph in another Carmen for Herbert von Karajan, with Leontyne Price and Franco Corelli. Among other superstar recordings from the Met's Golden Age, Merrill's lustrous baritone graced major roles in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Cavalleria Rusticana, I Pagliacci, Il Trovatore, Rigoletto (twice), La Traviata, and Sir Georg Solti's 1962 Aida with Leontyne Price, Rita Gorr, and Jon Vickers -- often cited as among the half-dozen or so greatest takes on this oft-recorded perennial. In addition to the Beecham recording, he also appeared in a notable disc version of La bohème opposite Anna Moffo and Richard Tucker, conducted by Erich Leinsdorf. It goes without saying that his work was a vital part of what made the Met's Golden Age so golden; he was highly valued there for his vigorous, powerful, and technically unshakable singing, if not for his acting skills (which were never a priority). In 1993, he was awarded the United States Medal of Arts.

Merrill recalls, as an eight-year-old, having been let in to the outfield to see Babe Ruth play. "Well, he was the Caruso of baseball and I never forgot that feeling." Appropriately, in 1986, for the Yanks' opening game at Yankee Stadium, Robert Merrill became the first person ever to both sing the Star Spangled Banner and throw out the first ball. He continued to appear at Yankee Stadium occasionally until a few years before his death on October 23, 2004.

An eminent opera singer, bass-baritone Giorgio Tozzi was also thoroughly at home in American musical theater. He began to study singing at the age of thirteen. Entering Chicago's DePaul University with the intention of becoming a biologist, he changed his mind and studied voice with Rosa Raisa, Giacomo Rimini, and John Daggett Howell. His operatic debut was in the American premiere of Benjamin Britten's chamber opera The Rape of Lucretia, as Tarquinius, which was a 1948 Broadway production rather than an opera presentation. In 1949, he went to London to sing in a musical, Tough at the Top. He remained in Europe to study in Milan with Giulio Lorandi. Tozzi's Italian debut was at Milan's Teatro Nuovo as Rodolfo in La sonnambula; his La Scala debut was in 1953, in Catalani's La Wally. He returned to the United States, where his first appearance at the Metropolitan Opera was in 1955, in La Gioconda. Tozzi then joined the Metropolitan company, staying there until 1973. As his operatic career developed, Tozzi maintained a keen interest in musicals, starring in several acclaimed productions. His performance in the Broadway revival of Most Happy Fella brought him a Tony Award nomination for Best Actor in a Musical. In 1957, Tozzi won the Critics' Award for Best Actor in a Musical for the production of South Pacific in San Francisco, opposite Mary Martin. He was also on the sound track of the film South Pacific as the voice of Emile Debeque, acted by Rosanno Brazzi. The soundtrack of that film brought Tozzi a gold record from RCA Victor, and he also won three Grammy Awards. In 1958, he created the role of The Doctor in the world premiere of Samuel Barber's Vanessa at the Met. Other roles in his repertoire were the title role in Musorgsky's Boris Godunov, King Philip in Don Carlo, Mephistopheles in Gounod's Faust, the title role of Don Giovanni, Gremin in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin, Don Basilio in Rossini's Barber of Seville, Gurnemanz in Parsifal, Arkel in Debussy's Pélleas et Mélisande, Figaro in The Marriage of Figaro, King Marke in Tristan und Isolde, and Hans Pogner in Die Meistersinger. Tozzi's appearance in the Hamburg Opera's film Die Meistersinger, as Hans Sachs, is, he says, his proudest professional achievement. He also filmed his roles as Boris Godunov and as King Melchior in Menotti's Amahl and the Night Visitors. Tozzi performed in all the great opera houses. In his 20 years with the Metropolitan, he sang 400 performances. In addition to his work in operas in musicals, Tozzi often appeared on film and television in singing and non-singing roles. Throughout his career, Tozzi was an enthusiastic teacher, always eager to encourage younger musicians. During his tenure at the Met, Tozzi taught at the Juilliard School in New York City. In 1991, became a professor at the Indiana University School of Music. Tozzi died in Bloomington, Indiana at the age of 88.

Regarded as a useful house conductor during his many years at the Metropolitan Opera, Fausto Cleva died before he saw his reputation grow to the more generous assessment that prevailed decades later. Always known as a singer's maestro, Cleva was also a conscientious interpreter of bracing urgency, a shrewd mentor, and an individual of integrity. Cleva's studies began at the conservatory in his native Trieste and continued in Milan. Shortly after he had made his debut at Milan's Teatro Carcano in 1920 conducting La traviata, Cleva traveled to America, almost immediately beginning his long association with the Metropolitan Opera. Serving as an assistant conductor from 1920 to 1925, and again from 1938 to 1940 (he served two stints as chorus master, as well, from 1935 to 1938 and in 1940 and 1941), he waited until February 14, 1942, to be assigned a performance of Rossini's Il barbière di Siviglia. Although reviews were laudatory, further opportunities seemed too doubtful to keep him in New York. Cleva departed to attend to other engagements, most notably at the Cincinnati Summer Opera, where he served as music director from 1934 to 1963. Other major American companies welcomed him as well. He conducted in Chicago (where he led performances from 1942 until the demise of the Chicago Opera in 1946, receiving especially good reviews for his leadership of the 1944 opening-night Carmen) and in San Francisco, strengthening that conducting roster beginning with a 1942 La traviata with Bidú Sayão. His position in the Italian wing of the San Francisco Opera substantially grew in the early '50s until his return to the Metropolitan as a full-fledged conductor expanded to keep him largely in New York. Cleva's November 13 direction of the Aida that opened the 1951 - 1952 Metropolitan season was regarded as the most sharply realized to have been heard in years, strongly cast with Milanov, del Monaco, and London. Concentrating on the Italian repertory with frequent excursions into the French, Cleva amassed a total of 677 Metropolitan Opera performances before his death while leading an Athens outdoor performance of Gluck's Orfeo et Euridice in 1971. Among Cleva's too-few recordings, a sumptuously cast Luisa Miller is a worthy memento of an underrated conductor.

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?