Die Walk├╝re

ÔäŚ┬ę 2021: Walhall Eternity Series

Artist bios

Lotte Lehmann was one of the top dramatic soprano vocalists during the first half of the 20th century. She was known for her exuberant sense of drama, imaginative phrasing, and a precise vocal technique.

Lehmann was born in Perleberg, Germany, in 1888 to a modest and musical family. Her father sang folk music with the local glee club, and he also played the zither. Her mother and aunt also sang, but they both suffered from health problems that prevented them from performing professionally. As a child, she took piano lessons, dance lessons, and she also enjoyed painting. In 1902 Lehmann moved with her family to Berlin, where she studied singing with Mathilde Mallinger, the famous Croatian soprano. Her father encouraged her to pursue other more practical career options, but Lehmann was determined to become a singer and continued with her musical studies. She began her first professional appointment in 1910 and sang minor roles with the Hamburg Opera. However, she learned the profession quickly and began singing important roles early in her career.

In 1914, Lehmann made her first recordings, and she gave debut performances in London with Thomas Beecham and the Covent Garden Opera, and in Vienna with the Vienna State Opera. Two years later, she moved to Vienna and joined the Vienna State Opera, where she sang the premieres of several operas by Richard Strauss, including Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, and Intermezzo. Lehmann remained in Vienna for 21 years and sang over 50 roles with the Vienna State Opera. From 1924 to 1935, she sang with the Covent Garden Opera and became very popular in London. She was also the inspiration for the musical The Sound of Music, when she discovered the Trapp Family Singers and convinced their father to let them perform in public in 1936. She made her American debuts with the Chicago Lyric Opera in 1930, and with the Metropolitan Opera in 1934 and returned to the U.S. annually to perform. It was also around this time that she began singing lieder and art songs, accompanied by Bruno Walter, Erno Balogh, and eventually Paul Ulanowsky.

In 1938, Lehmann relocated to the United States to distance herself from the Nazi regime and performed regularly with the Met until 1945. This was followed by an additional season with the San Francisco Opera before her partial retirement in 1946. She continued performing in recitals until 1951 and began a new career as a professor at the Music Academy of the West, in Santa Barbara. She retired from her teaching position in 1962, and spent her final years painting, writing, and she gave private lessons in her home. Her literary works include volumes on musical interpretation, a novel, and an autobiography. Lehmann passed away in 1976 at her home in Santa Barbara. ~ RJ Lambert

The spirited dramatic soprano Marjorie Lawrence was becoming an increasingly important figure in Wagnerian circles when she was stricken with polio in 1941. The misfortune was made all the more poignant by Lawrence's vaunted athleticism which previously had encouraged her to appear with a real horse in G├Âtterd├Ąmmerung, riding it into the flames as Wagner had envisioned. Her attempts to return to the stage were thwarted by certain Metropolitan patrons who found the sight of a singer not fully mobile "unseemly." Thus, her post-attack suitability for such roles as Isolde and Venus came to naught. She did make a successful return to Paris in 1946 as Amneris, but gradually her singing career diminished as she entered into a new phase as a respected teacher. Her story was the subject of a widely viewed motion picture, Interrupted Melody.

Lawrence was born in a small Australian town a hundred miles from Melbourne; her parents were sheep ranchers. An enthusiastic singer as a child, Lawrence entered a voice competition in Melbourne and won; she followed that victory with intensive studies with Ivor Boustead. Her father, at first opposed to her becoming a singer, eventually consented to sending her to Paris when the noted Australian baritone John Brownlee suggested the move.

In Paris, Lawrence studied with C├ęcile Gilly for three years before making her operatic debut in Monte Carlo as Elisabeth in a 1932 production of Tannh├Ąuser. Her success there led to a contract offer from the Paris Opera and, only weeks after her very first appearance on stage, she was introduced to Paris audiences in Lohengrin. Soon thereafter, she sang the title roles in Salome and Aida, and remained with the company for three years, during which she sang the standard dramatic repertory and such relative rarities as Br├╝nnhilde in Ernest Reyer's Sigurd, Valentine in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots, Salom├ę in Massenet's H├ęrodiade, and Keltis in the world premiere of Canteloube's Vercing├ętorix.

On a visit to Europe in 1935, recently appointed Metropolitan Opera manager Edward Johnson heard Lawrence and immediately engaged her for New York. The attractive soprano, still well shy of 30, made her Metropolitan debut on December 18, 1935, as Br├╝nnhilde in Die Walk├╝re, impressing critics as a splendid addition to the company. Lawrence Gilman wrote, "She has temperament and brains. She has a beautiful profile. She has an admirable sense of costume, a feeling for the stage, for the meaning of words and notes." Although her singing could not match the Olympian standards of Kirsten Flagstad, also newly arrived at the Metropolitan, it was nonetheless dynamic and bright-toned. Perhaps as a result of her French training, her Ortrud was felt to be lacking in seductive sound when she introduced that portrayal three days later, but her Br├╝nnhilde in Siegfried was felt to be promising. In her masterful singing of the G├Âtterd├Ąmmerung Br├╝nnhilde later that same month, she surprised the audience by actually mounting Grane and riding into the opera's consuming flames at the end of the immolation scene. As Rachel in La Juive just days later, she proved the efficacy of time spent in Paris with a well-sung, stylistically sensitive realization.

Lawrence's Metropolitan performances over eight seasons also embraced Alceste and Strauss' Salome in addition to her big Wagnerian roles. After being attacked by the poliomyelitis that left her paralyzed from the waist down, Lawrence devoted herself increasingly to concert performance.

Lauritz Melchior was the first of the great Wagnerian heldentenors (heroic tenors) to sing on records, and he was the first operatic tenor to sing on radio. His recorded legacy is considered a benchmark for all subsequent Siegfrieds and Tristans. One can only imagine what a legacy was lost when he and his wife fled Germany in 1939; his home there was subsequently occupied and looted by both German and Russian soldiers and a collection of unpublished recordings was used for target practice. Contemporary reviews indicated that he was frequently lax in keeping rhythms, and many of his debuts were not completely successful, but he had a long operatic career.

Melchior started singing at an early age, when a boarder in his father's house who was a voice teacher gave Melchior and the other children in the family singing lessons. He often accompanied his sister (who was blind) to the opera, and from her reactions he learned how dramatically powerful a voice can be, even without stagecraft. Like many Wagnerian and heroic tenors, he started his career as a baritone (and very briefly as a bass), first studying privately with Paul Bang, and after he turned 21, studying at the Copenhagen Royal Opera School. His unofficial debut was in 1912 as Germont in La Traviata with a tiny touring company, the Zwicki and Stagel Opera Company, and he made his official debut in 1913 as Silvio in I Pagliacci at the Royal Opera. He remained there for several seasons, first in comprimario roles, and later in major roles, beginning what looked like a solid career as a Verdi baritone when singing di Luna in Il Trovatore and the elder Germont in La Traviata.

A colleague heard him take an unwritten high C in Il Trovatore one evening and told the directors of the Royal Opera she heard the foundation of a heldentenor in Melchior's voice. The management agreed and made arrangements for him to restudy his voice with the tenor Wilhelm Herold. He made his debut as a tenor in 1918 as Tannhauser, again at the Copenhagen Royal Opera. However, he was still uncertain of his technique and voice. In 1919, a wealthy patron encouraged the conductor Henry Woods to audition him, and he had his London debut at the Proms in 1920. He came to the attention of another patron, Hugh Walpole, the noted author, who provided Melchior with a generous allowance to further his studies as well as support his family. His Covent Garden debut was in 1924 as Siegmund. He auditioned for Siegfried Wagner (the son of the composer) and made his Bayreuth debut in 1924 as Parsifal. He continued to take leading roles there, including the legendary 1930 Tristan und Isolde under Toscanini, who dubbed him "Tristanissimo," until shortly before World War II. His Metropolitan debut was in 1926 as Tannhauser and he sang there regularly until 1950, when one of Rudolf Bing's first actions as general manager was to decline to renew his contract. This was partly for extra-musical reasons, including a predilection for practical jokes and appearing on "low brow" venues such as radio comedy and variety shows with Fred Allen and Bing Crosby, and partly for a growing disinclination to attend lengthy rehearsals.

After this dismissal, Melchior retired from the stage, though he continued to appear in films and operettas, sang on the radio (including a broadcast of the first act of Die Walk├╝re from Copenhagen on his 70th birthday), and as part of his own touring music company.

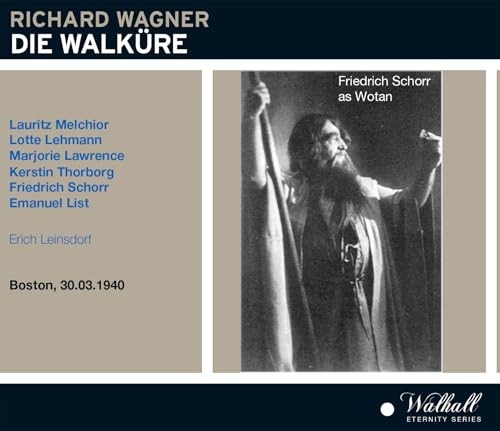

Friedrich Schorr set the standard for Wagnerian heldenbariton singing for the two decades between 1920 and 1940. His mahogany-colored bass-baritone may have lacked ultimate freedom in the highest reaches of the great heroic roles, but its beautiful, firmly knit timbre and absolute steadiness (and the singer's mastery of legato) made mockery of the notion that Wagner must be barked and not sung. Whether in the reflective moments of Hans Sachs, Vanderdecken's despair or Wotan's angry outbursts, his control of dynamics and clarity of utterance made his characterizations both riveting and complete. In an age of great Wagnerian singing, he stood at the very forefront.

Schorr's father, an attorney, hoped for a career in law for his son. Friedrich won a compromise: if he continued studying law, he could study music as well. Enrolling at Vienna University, he trained under Adolph Robinson, who had been the first to recognize Schorr's vocal gifts. In a year's time, Schorr was heard by the intendent of the Graz Opera who invited him to make his debut in that venue. At the age of 23 and having disclosed nothing about the performance to his parents, the young singer sang the exacting role of Wotan. Armed with the positive reviews, Schorr traveled to Vienna to show his father the contract that had been his reward. The budding heldenbariton was given his father's blessing to become a professional singer and his career began in the deepest waters of the bass-baritone repertory.

Schorr remained at Graz from 1911 to 1916, appearing often as a guest at the Vienna Opera where he quickly became a favorite with its discerning public. From 1916 to 1918, he was a member of Prague's National Theatre, after which he spent five years at Cologne. From 1923 to 1932 (and the rise of Hitler), Schorr was a leading artist in Berlin not only in the Wagnerian wing, but in such other roles as Busoni's Faust, Cardinal Borromeo in Pfitzner's Palestrina, and Barak in Strauss' Die Frau ohne Schatten. During this same period, beginning in 1925, Schorr was a frequent performer at the Bayreuth Festival. Even though his being a Jew was tolerated by Nazis prior to their ascension to power, Schorr ended his affiliation with Bayreuth in the same year he took leave of Berlin.

Meanwhile, Schorr visited the United States in 1924 with a company presenting a season of Wagner operas at the Manhattan Opera House. Metropolitan Opera manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza heard him and offered a contract, beginning an association that lasted until the singer's retirement in 1943. Following his debut on February 14 as Wolfram, Schorr offered his Hans Sachs, described by Lawrence Gilman as a "truly great performance" and similarly praised by the other New York critics. London, too, benefited from Schorr's artistry in the years from 1924 to the outbreak of WWII. After eliciting enthusiasm for the Rheingold Wotan which served as his debut, he roused the London audience to fervent applause for his superlative Walk├╝re Wotan, both wrathful and ruminative, sung throughout with the utmost beauty of tone.

Though no complete role of his was recorded during his prime, Schorr left an estimable legacy of Wagnerian excerpts, performed with such other titans as Frida Leider and Lauritz Melchior. His single contribution to Walter Legge's Hugo Wolf Society Lieder recording series, Prometheus (performed in the orchestral version), would alone secure Schorr's reputation among the immortals.

During the late 1920s and the 1930s, a period remembered as one of the golden ages of Wagnerian singing, Emanuel List (born Emanuel Fleissig) was counted as among the finest of basses and specialized in the villain roles in the operas of Wagner and others. He was tall and physically imposing, adding a commanding and dangerous element to his rich, deep, and dark singing tone.

He started his singing career as a boy soprano in the chorus and some solo work on the roster of the Theater an der Wein in Vienna. His family moved to the United States, where he was a vaudeville singer while studying voice with Josiah Zuro.

He returned to Vienna in 1920 for more training and to further his singing career, and soon made a debut at the Volksoper in 1922 in the major role of Mephistopheles. He moved to Berlin in 1923 to accept an engagement as a member of the Charlottenburg opera company, and joined the company of the Berlin State Opera (Staatsoper) in 1925. In the same year, he made a Covent Garden debut as Pogner in Die Meistersinger. He remained a member of the roster of the Staatsoper, making a specialty of such Wagnerian roles as King Mark (Tristan und Isolde), Hunding (Walk├╝re) and Hagen (G├Âtterd├Ąmmerung), as the implacable high priest Ramfis in Verdi's Aida, and in his most famous role, Baron Ochs in Richard Strauss' Der Rosenkavalier. He began singing in the Salzburg Festival in Austria, taking the Mozart roles of Osmin (Abduction from the Seraglio), and the Commendatore (Don Giovanni), and Rocco in Beethoven's Fidelio, in addition to King Mark. He appeared in the 1933 Bayreuth Festival as Hunding and Hagen, in addition to Fafner as the giant in Rheingold and as the voice of Fafner's transformed shape of the Dragon in Siegfried. As a Jew, he prudently left German in 1933 and made his debut that year at the Metropolitan Opera in New York as the Landgrave in Tannh├Ąuser. He was a member of the Met company from that year until 1950, and also sang regularly at the opera houses of San Francisco, Chicago, and Buenos Aires, and became a naturalized American citizen. Shortly before retiring, he made his first appearance in nearly 20 years in Berlin in 1950.

Among his famous recordings are performances as Hunding in the cutting of the complete first act of Die Walk├╝re, and as King Mark in the equally famous 1936 Melchior-Flagstad Tristan und Isolde.

Erich Leinsdorf was one of the most respected (if not always well-liked) European-born conductors and music directors to achieve prominence in America after World War II. An acclaimed operatic conductor, whose recordings of Turandot and Madame Butterfly from the end of the 1950's remain among the most popular in the catalog, his reputation as a conductor of orchestral music hasn't survived quite as well.

He was born Erich Landauer in Vienna, Austria, and by the age of five was enrolled in a local music school, beginning piano studies at age eight. He subsequently studied at the music department of the University of Vienna, and from 1931 until 1933 took courses at the Vienna Conservatory, making his debut at the podium at the Musikvereinsaal upon graduation. He became the assistant conductor of the Workers' Chorus in Vienna in 1933, and a year later successfully auditioned before Bruno Walter and Arturo Toscanini at the Salzburg Festival, where he was appointed an assistant, serving under Toscanini.

Leinsdorf was engaged by the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1937, and his American debut took place there, at age 25, when he conducted Wagner's Die Walkure on Jan. 21 of 1938. His success with other Wagner operas led to his appointment at the Met in 1939 as head of the company's German repertoire. It was while at the Met that he began developing a reputation as a strict taskmaster, demanding more rehearsal time from his singers and extremely precise fidelity to the written score by his orchestras--although the audiences appreciated the results he achieved, many of the singers he worked with were highly critical of his work and the demands he made upon them.

He took American citizenship in 1942, and the following year he was appointed music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. He had no time to achieve much in the new post, however, as Leinsdorf was inducted into the United States Army in December of that year. He was discharged in 1944, and returned to the Met, where he conducted during the 1944-45 season. During 1945 and 1946, he also conducted the Cleveland Orchestra on several occasions, and returned to Europe where, as one of a group of major Austrian-born conductors who had no connections with the Nazis, he was engaged to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. He found his reception in the city of his birth, first overrun by the Nazis, then bombed and invaded by the Allies and starved in the immediate wake of World War II, however, to be less than entirely cordial.

By 1947, he was back in the United States as music director of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in upstate New York, a post he held until 1955. Leinsdorf served as music director of the New York City Opera for part of 1956, before returning to the Met as a conductor and musical consultant, amid numerous guest conductor assignments in America and Europe. In 1962, Leinsdorf succeeded to one of the most prestigious musical posts in America, as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, succeeding Charles Munch. Leinsdorf's tenure at Boston was extremely productive but stormy. He found the political considerations of a music directorship, juggling the demands of individual musicians, their unions and existing work and rehearsal rules, and the board of directors, to be a distraction from his musical goals. Additionally, it was during this period that Leinsdorf became known for being openly critical of the shortcomings, in terms of education, of the musicians working under him (especially gaps in their cultural educations), errors in published scores of established musical works, and the errors made by his fellow conductors.

He resigned the Boston post with the 1968-69 season, happy to have served in one of the most exalted musical positions in the United States, but equally happy, in his own words, to have exited with his health intact. Leinsdorf conducted opera and concert performances throughout the United States and Europe for the next two decades, including work with the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic. In 1978, he took up his first permanent post in Europe, was principal conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra in West Berlin, a post he held until 1980. In 1976, he published Cadenza: A Musical Career, a memoir that was as noted for its candid, brutally honest assessments of himself and his fellow musicians as for the biographical details it offered. He continued recording until the final years of his performing career, at the end of the 1980's, including audiophile digital performances of Wagner orchestral music for the Sheffield Labs label.

Erich Leinsdorf's greatest operatic achievements on record, Turandot and Madame Butterfly, remain in print on compact disc more than 30 years after they were recorded, but his orchestral recordings haven't fared as well. Mostly confined to RCA/BMG with the Boston Symphony, a relative handful of these have appeared on budget CD reissues (mostly BMG's "Silver Seal" label), including a Mahler Fifth Symphony that is no longer really competitive with other versions out there (at the time it was recorded in the mid-1960's, it was one of perhaps four or five versions, not one of 60 as it is today); ironically, his Mahler Symphony No. 3, one of the finest things he ever did, and one of the better performances of this monumental work ever done, remains out-of-print, and well worth owning on vinyl. ~ Bruce Eder

Mahler Symphony No. 5 RCA/BMG [5]

Symphony No. 3 RCA [8] (out-of-print)

Mozart Don Giovanni London [7]

Puccini Madame Butterfly RCA/BMG [7]

Turandot RCA/BMG [8]

Customer reviews

How are ratings calculated?